University of North Carolina Hillsborough Hospital

Theresa Sivers-Teixeira, MSPA, PA-C, Erin Thayer, MPH, and Jennifer Clurman, RN

University of North Carolina (UNC) Hillsborough Hospital (HBH) is a community-based hospital located in rural Orange County 10 miles north of the UNC Medical Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. HBH has 83 hospital beds and 15 emergency department beds and serves approximately 23,000 patients per year, about 20% of whom are older adults. HBH is the first and only Level 2 accredited geriatric emergency department (ED) in the state of North Carolina and is recognized by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement as an Age-Friendly Health System. UNC has a strong history of engagement in elder mistreatment work, including a National Institute of Justice-funded study aimed at developing and validating the ED Senior Abuse Identification tool at UNC Medical Center. HBH functions as an extension of UNC Medical Center, served by many of the same faculty and staff. By implementing the Elder Mistreatment Emergency Department (EMED) Toolkit at HBH, UNC sought to continue to play a vital role in development and refinement of tools used to identify and respond to elder mistreatment.

Addressing Elder Mistreatment Prior to Toolkit Implementation

Prior to implementation of the EMED Toolkit, HBH did not systematically screen or track suspected elder mistreatment specifically. However, ED triage nurses at HBH utilized a general screening tool that asked all adult patients, regardless of age, whether they felt safe at home, and whether anyone was financially exploiting them and/or physically or sexually abusing them. If a patient screened positive, physicians, nurses, social workers, and case managers within the ED used existing connections to refer patients to Adult Protective Services (APS) and other community resources, such as UNC Hospital’s Beacon Program in Chapel Hill. If a bedside nurse suspected some form of elder mistreatment, that suspicion was reported to the attending physician and the patient experiencing suspected mistreatment was referred to an ED case manager, who made a report to APS if deemed appropriate. If a patient, who screened positive for suspected mistreatment, was admitted to inpatient services, the bedside nurse conveyed concern for elder mistreatment to an inpatient social worker who then reported the case to APS, if appropriate. Both APS and UNC Hospital’s Beacon Program provided patients suspected of being mistreated with additional evaluation, counseling, support, consultations, information, resources, referrals, and training. HBH generated referrals to these resources for a variety of reasons and did not track data related to cases of suspected elder mistreatment and ED response specifically.

At HBH, 50 ED staff members were invited to participate in the baseline Elder Mistreatment Emergency Department Assessment Profile (EM-EDAP) during the summer of 2019. In total, 34 staff members—representing 68% of active ED staff—responded, including 3 medical staff members (attending physician, nurse practitioner, resident), 20 nursing staff members, 9 ED patient care technicians, one cardiology technician, and one scribe. No social workers participated in the baseline EM-EDAP. This assessment revealed that only 26% of respondents had received some formal education on elder mistreatment detection, management, or reporting. Almost half of respondents (48%) did not feel confident in their abilities to recognize elder mistreatment. Less than a quarter of respondents considered themselves knowledgeable about best practices for identifying cases of suspected elder mistreatment. Staff reported that the greatest barrier to addressing elder mistreatment in the ED was communication difficulties with older adults. Responses to questions about community resources suggested that there were few resources for older adults at risk of or experiencing elder mistreatment.

Implementing the Toolkit to Address Elder Mistreatment

Most ED nursing staff participated in a training on how to use the new screening tool. The type of training depended on what role staff were expected to play in the screening and referral process. Sixty-seven percent of ED nursing staff participated in a 30-minute online training in which they learned how to implement the brief screen embedded in the Elder Mistreatment Screening and Response Tool (EM-SART) and 93% of ED nurse case managers participated in a 60-minute online training on how to implement the more in-depth EM-SART full screen. The ED clinical champion participated in a comprehensive 4-hour online training on elder mistreatment. Notably absent from training were social workers who were expected to respond to suspected cases of elder mistreatment as indicated by the EM-SART full screen; only one social worker completed the full screen implementation training. Training participants completed pre- and post-training questionnaires to assess changes in knowledge, attitudes, and efficacy about how to address elder mistreatment using the EM-SART. In general, staff mean scores associated with the brief screen training increased from pretest (4.87) to posttest (6.40 with highest possible score being 10) as did scores associated with the full screen training (10.43 to 11.86 with highest possible score being 20). Persisting gaps in knowledge post-training included: recognizing situations that could indicate elder mistreatment, recognizing caregiver behaviors that may indicate elder mistreatment, recognizing patient behaviors or physical presentations that may indicate elder mistreatment, conducting full screens for suspected cases of elder mistreatment, and discharge procedures for suspected cases of elder mistreatment.

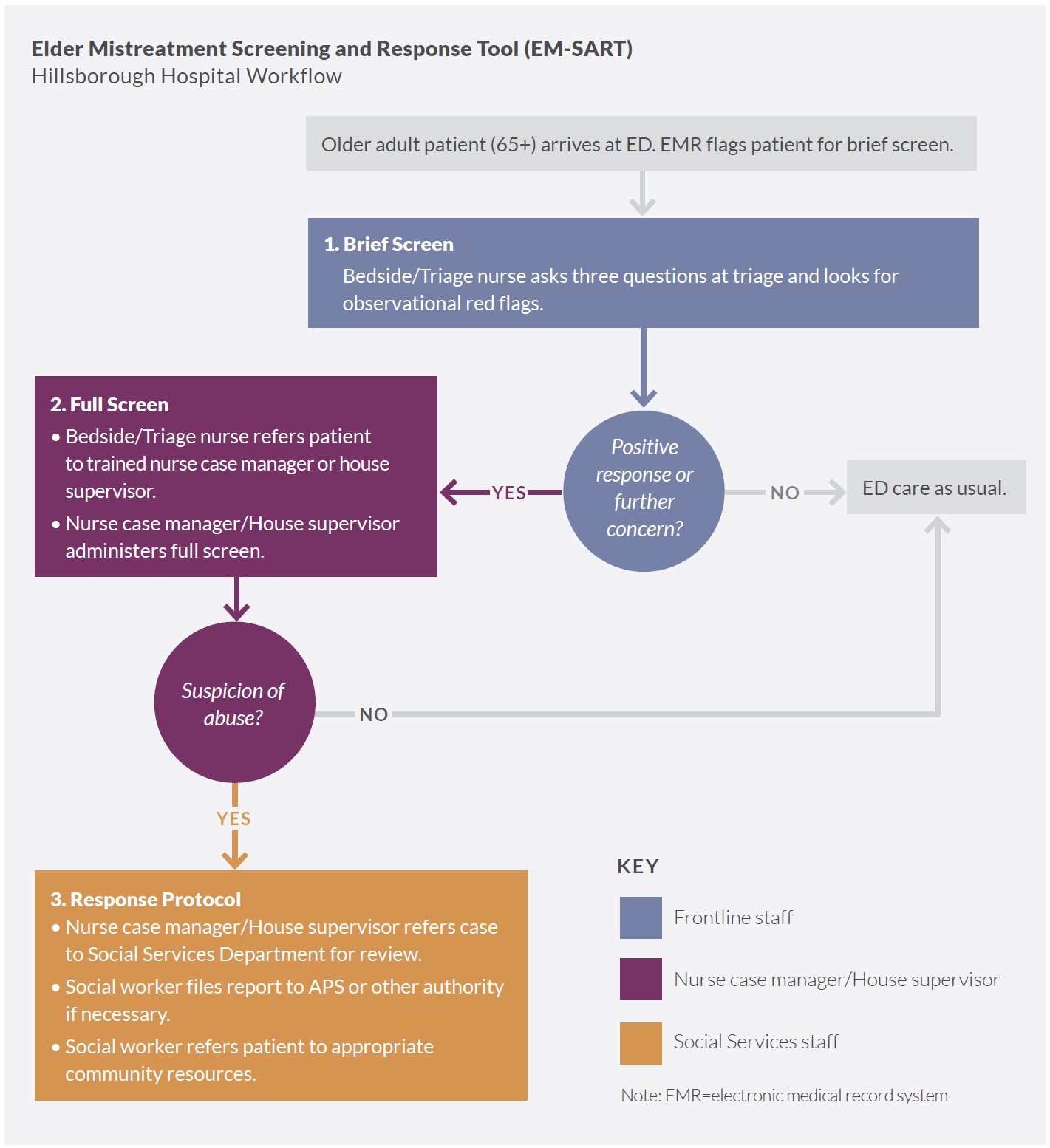

ED bedside nurses conducted both brief and full screens. During the 9-month implementation phase, trained triage or bedside nurses administered the brief screen for elder mistreatment to adults aged 65 years or older who presented in the ED. When the brief screen indicated possible mistreatment, a nurse case manager, house supervisor, or one of six trained nurses completed the full screen. When full screens were positive, the nursing staff notified the social worker, who then provided the appropriate response and referrals.

HBH began improving communication with APS. When considering level of service integration and network functioning on a continuum from reporting to connecting to collaborating, HBH is categorized as being at the connecting stage, in which they are engaging community resources beyond APS, and are moving toward collaborating, in which they will formalize an elder mistreatment team. The HBH clinical champion used the EMED Toolkit’s Community Connections Roadmap to connect with various stakeholder organizations interested in furthering a community response to elder mistreatment. Stakeholders included: Piedmont Triad Regional Council Area Agency on Aging; UNC Hospital’s Beacon Program; North Carolina Department of Justice; UNC Division of Geriatric Medicine; Orange County Department of Social Services, APS; and Self-Help Credit Union. Dialogue among stakeholders surfaced a number of issues: APS lacks the capacity to handle all elder abuse and mistreatment cases, Area Agencies on Aging have additional tools to address elder abuse and mistreatment, and several entities have a financial interest in identifying elder mistreatment (e.g., APS, financial institutions, and consumer protection organizations, as well as accountable care and managed care organizations and payers). Stakeholders recommended creating a formal mechanism for sharing information about cases of suspected elder mistreatment that is both efficient and respects a patient’s right to privacy. Though participants agreed that frequent communication among stakeholders was critical, no other meetings took place formally or informally during the 9-month implementation period.

Factors Affecting Toolkit Implementation

HBH is committed to improving geriatric care. As a Level 2 accredited geriatric ED and Age-Friendly Health System, leadership was supportive of implementing a tool that aimed to improve the quality of care provided to older adults. Like nursing staff in many EDs, nursing staff at HBH played a significant role in establishing the culture of the ED. Having a well-respected nurse as a clinical champion and advocate was influential in recruiting nursing staff to participate in the brief and full screen trainings.

HBH integrated the brief screen into its electronic medical record system (EMR). Using a paper-based screening impeded ease of implementation. Over time, nursing staff modified the EM-SART by creating “open phrases” to allow for ad hoc integration into the EMR. The workflow was adapted to allow nurses to partially administer the full screen and then pass it on to their social work colleagues to complete and interpret.

Some duplication of workflows resulted given existing screening tools. Initial implementation of the EMED Toolkit was greeted with enthusiasm by HBH clinical staff. However, a preexisting protocol for screening all adult patients for mistreatment resulted in some duplication of workflows and “bedside screening fatigue.” This preexisting screening protocol was embedded in the EMR and required staff to complete prompts in order to continue assessing the patient. Thus, during this implementation period, nurses were required to complete both screenings.

Toolkit implementation did not integrate social work. Additionally, the preexisting protocol directed case managers to hand off positive screens to social workers to complete the assessment and response. Consequently, many positive brief screens were not handed off to the clinical champion as planned, but to social workers. These social workers were not trained on the EM-SART, resulting in assessments that did not consistently comport with the content of the full screen and response protocol in this project.

Fewer older adults presented in the ED during COVID-19. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 had a profound impact on both the number of older adults seen in the HBH ED and the consistency of screening rates. Rates varied month to month with the lowest in October 2020 (16%) and the peak in July 2020 (28%). Nonetheless, clinical staff persisted in implementing the protocol despite several COVID-19 surges impacting the ED during the implementation period.

Results of Implementation

Focused screening activities identify suspected cases of elder mistreatment. The patient-level screening results of the 9-month EM-SART implementation (February 2020 – October 2020) showed that the brief screen was administered to 20.8% of patients aged 65+ who received care during the implementation period. Among those screened, 4% were positive. Ninety-two percent of patients with a positive brief screen received a full screen. In total, there were 7 positive full screens which included 5 patients found to be in immediate danger. It is difficult to know how these figures compare to previous detection rates at HBH because, as noted above, ED staff screened for physical abuse for all patients presenting in the ED prior to EMED Toolkit implementation. However, EMED Toolkit implementation clearly resulted in administration of brief screens tailored more to the specific risk factors for older patients, and comprehensive screens of patients whose brief screen suggested mistreatment.

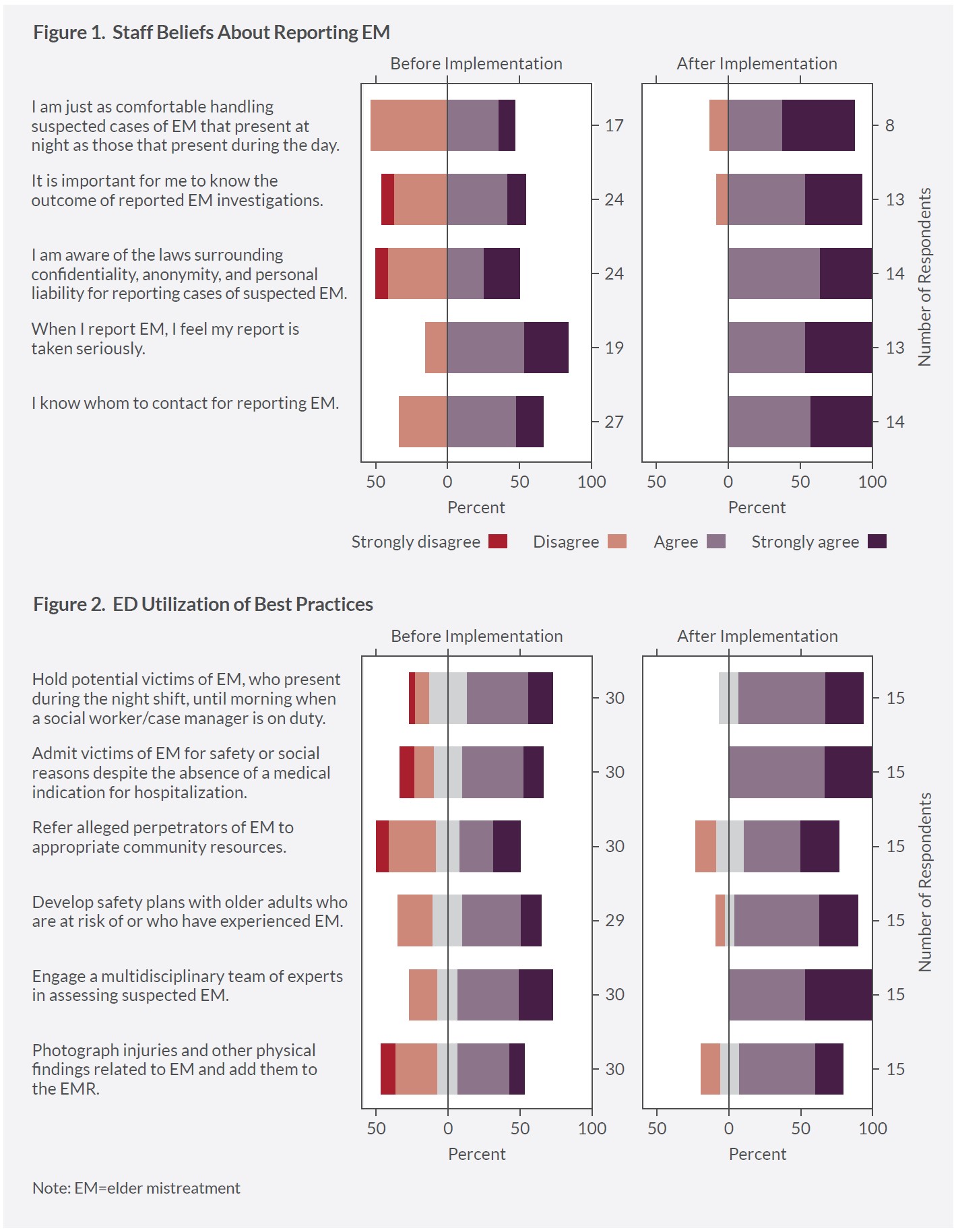

ED staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices about how to address elder mistreatment improved. Comparing EM-EDAP results prior to and after implementation show several important changes. HBH ED staff perceived greater confidence and felt more knowledgeable about best practices for identifying and responding to cases of suspected elder mistreatment, as well as greater awareness of the laws regarding confidentiality, anonymity, and liability. Overall, survey respondents indicated support of screening and response in the ED. Most respondents agreed that elder mistreatment is a common and serious problem, all older adults should be screened for elder mistreatment, and staff should report suspected elder mistreatment to APS. ED staff feel that APS is receptive and helpful when they report elder mistreatment.

In general, staff reported greater awareness of the lack of community resources for older adults at risk of mistreatment, acknowledged the value of multidisciplinary teams to manage patients, and recognized the positive role of APS and law enforcement when abuse is suspected. In focus groups and interviews, staff reported that the EM-EDAP and training were useful and beneficial in helping to raise awareness about elder mistreatment and identifying suspected cases of mistreatment. They noted improvements to practice, including better internal communication about suspected cases of mistreatment, higher screening rates, increased staff awareness about elder mistreatment, and increased staff knowledge of how to handle suspected cases of elder mistreatment.

Toolkit implementation does not disrupt ED functions. Training, new screening protocols, and additional community connections activities resulted in few significant changes in ED functioning, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The percentage of older adult patients returning to the ED 30 days post ED discharge and the percentage of older adults admitted to inpatient services from the ED remained constant. Mean and median length of stay varied within the pre-implementation and implementation periods, most likely due to COVID-19 case rates, but did not differ significantly between pre-implementation and implementation. The percentage of older adults admitted to the hospital (32% pre-implementation vs. 32% during implementation) and 30-day returns to the ED (23% pre-implementation vs. 24% during implementation) were identical or slightly higher during the implementation period, suggesting that EMED Toolkit implementation did not have an adverse impact on ED functioning.

Key Lessons Learned

Great strides were made in knowledge and confidence through the training provided in the program, and participants expressed a strong desire for more training on defining elder mistreatment, community resources for patients experiencing elder mistreatment, detection and reporting, handling issues related to self-neglect, and identification in the presence of cognitive impairment.

Most positive brief screens were marked positive based on observations rather than positive answers to the screening questions, and more than half of the positive full screens at HBH had physical findings—predominantly bruising and signs of neglect—noted during the initial bedside exam. This may signal that forms of elder mistreatment without visible physical findings may have gone undetected. The clinical champion suggested that integrating a tool, such as a diagram of the body, would support efficient and accurate documentation of physical findings. In the four cases with concern for sexual abuse, the full screens were incomplete and without follow-up of labs or appropriate physical exams. This indicates that more complete screening could be achieved with greater medical provider contribution in the clinical work-up and decision-making regarding the dissociation of factors related to normal aging or self-neglect versus injury or abuse. Due to the organic evolution of the protocol at HBH, it became apparent that social workers need to receive training to become fully integrated into screening and response protocols. Cultivating an EM-SART social work clinical champion may facilitate this effort.

Also, for the elder mistreatment screening protocol to be sustainable, it is critical that it be integrated into the EMR. Without this essential functionality, screening will not be universal or complete and older adult victims will not be successfully identified and cared for. Yet, it is difficult to know how the number and percentage of elder mistreatment cases found when using the EM-SART compare to previous detection rates at HBH because, as noted above, ED staff administered a brief screen on physical abuse to all patients presenting in the ED prior to EMED Toolkit implementation.

In terms of establishing community connections to address the needs of those at risk of or experiencing elder mistreatment, HBH was able to network with and assemble local stakeholders to discuss roles, responsibilities, challenges, and contributions of each. However, stakeholders did not continue to meet after an initial convening. As noted by the HBH clinical champion, EDs will need additional and practical education that outlines specific strategies to build and sustain a diverse group of stakeholders that will work together to address elder mistreatment.

Follow-up and the Future

HBH staff remain dedicated to identifying elder mistreatment in their ED as part of their commitment to being an accredited geriatric ED in an Age-Friendly Health System. Despite the challenges the COVID-19 pandemic presented during the study, they emphasized the value of elder mistreatment training and predict broader and more consistent use of the EM-SART once it is integrated into the EMR.

“I think that when you implement anything, especially something that’s as important as this . . . and it’s rolled out in a way that people understand that it’s for the betterment of the patients, then they’re now — and probably forever will be — aware . . . It’s going to be part of their practice now.“

–HBH ED staff member

About the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment and EDC

With funding from The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment was founded in 2016 with a charge to develop a scalable response to the prevalence of elder mistreatment. This group is comprised of national experts in elder mistreatment from the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and Joan & Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University, with Education Development Center (EDC) serving as the Collaboratory convener, EDC is a global nonprofit with more than 60 years experience designing, testing, and implementing innovative programs addressing critical challenges in health, education, and economic inequality.

To learn more: contact us at NCEAEM@edc.org or visit https://www.edc.org/national-collaboratory-address-elder-mistreatment