Heywood Hospital

Debi Lang, MS, Joan Doyle, RN, CEN, Carol-Lynne Papa, RN, and Barbara Nealon, LSW, CHW, CDVC, CCJS, SWAC

Heywood Hospital is a 134-bed community hospital located in the small city of Gardner, Massachusetts. The hospital is part of a health care system that offers comprehensive primary care and specialty services in north central Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire. Its emergency department (ED) serves approximately 26,000 patients each year. Heywood is a major rural healthcare provider and is committed to addressing critical public health issues. Its team of clinical champions includes Director of Infection Prevention & Control and former ED Director Joan Doyle, Practice Leader Carol-Lynne Papa, and Social Services Director Barbara Nealon.

Addressing Elder Mistreatment Prior to Toolkit Implementation

Heywood came to the attention of the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment through a preexisting relationship with Massachusetts Executive Office of Elder Affairs. There, Heywood had established a reputation as a “small but mighty” facility with a strong commitment to safeguarding the health and wellbeing of the older adults in their catchment area. Clinical champions from Heywood participated in a planning meeting hosted by the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment in September 2017. At this meeting, they provided practical guidance that informed the design and development of the Elder Mistreatment Emergency Department (EMED) Toolkit. At that time, their concerns for older adults in their community included isolation due to limited access to transportation, lack of behavioral health resources, and high suicide rates.

When asked about the ED’s role in addressing elder mistreatment, Heywood emphasized their goal was to treat medical emergencies and then discharge patients to the “most appropriate, safe setting.” However, staff noted that community service providers (e.g., nursing homes, home care, Adult Protective Services [APS]) sometimes viewed the ED itself as a safe setting to “hold” victims of mistreatment until an appropriate safety plan could be implemented. Heywood clinical champions reported that these differing perspectives signaled the need to raise public awareness about elder abuse and the importance of connecting older adults and their families to community-based resources appropriate to support their needs.

Prior to EMED Toolkit adoption, Heywood had no standard protocol for assessing and managing suspected cases of elder mistreatment in the ED, and nurses—with limited specialized training— were not regularly screening patients for abuse or neglect. In the year prior to EMED Toolkit implementation, ED nursing staff identified only two cases of suspected mistreatment. In such cases, nurses referred the patients to Heywood’s Social Services Department, who then followed up with the patients and submitted reports to APS when appropriate. However, with no internal feedback loop between Social Services and the ED, nursing staff were not kept informed about the outcomes of APS reports, creating a sense of frustration among the nurses.

Baseline Elder Mistreatment Emergency Department Assessment Profile (EM-EDAP) findings indicated that Heywood staff felt they were effective in terms of recognizing, responding to, and intervening in suspected cases of elder mistreatment, but had several gaps in practice regarding referral to specialized community services for older adults vulnerable to mistreatment, reliance on family members or caregivers for medical and social historical information, and presence of a streamlined response to elder mistreatment.

Implementing the Toolkit to Address Elder Mistreatment

Nearly all bedside nursing staff participated in a training on how to use the new screening tool. Following the initial EM-EDAP, Heywood clinical champions decided that in order to better address elder mistreatment in the ED, they would need to engage nursing staff in screening activities. Almost all (95%) ED nursing staff participated in an hour-long online training on how to screen for elder mistreatment using the Elder Mistreatment Screening and Response Tool (EM-SART). Additionally, two clinical champions completed a more extensive online training. In the post-intervention EM-EDAP, staff demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge of, and confidence in, elder mistreatment recognition and intervention.

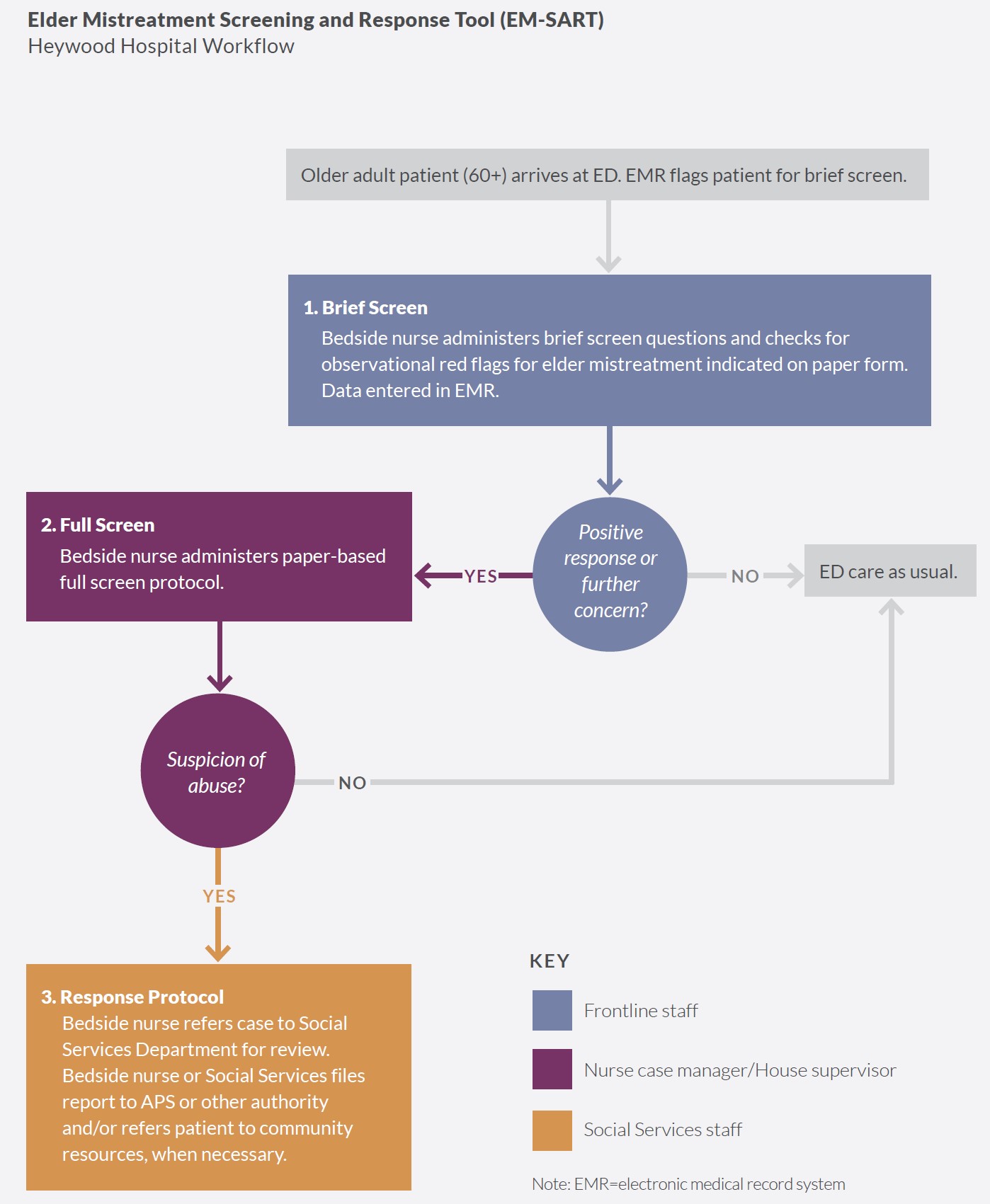

ED bedside nurses were responsible for screening and response. By February 2020, Heywood had established a new screening protocol that relied heavily on trained nursing staff. First, the electronic medical record system (EMR) flagged patients aged 60 years or older who registered in the ED. Bedside nurses then administered the brief screen to all flagged patients. They documented whether the brief screen raised concerns for mistreatment, and if further assessment was needed. If the brief screen was negative, meaning there was no suspicion of mistreatment, the patient received ED care as usual. If the brief screen was positive, indicating possible mistreatment, the same bedside nurse continued with the more extensive full screen portion of the EM-SART, using a paper screening form. If the full screen was positive, signifying there was suspicion of mistreatment and/or the patient needed additional services, the nurse documented the findings and referred the case to the Social Services Department for further review and referral. The nurse or Social Services staff submitted a report to APS when necessary. The figure below depicts the EM-SART workflow at Heywood.

Heywood collaborated with community agencies to address elder mistreatment. Prior to implementing the EMED Toolkit, many of the surveyed staff agreed there were insufficient community resources to either respond to or prevent cases of elder mistreatment (50% and 61%, respectively). To address these concerns, in May 2020, Heywood began using the Community Connections Roadmap, a planning tool to facilitate collaboration between hospital EDs and community-based services. They began by identifying and developing a list of community resources and service providers in the area who interact with older adults. Heywood was able to leverage several preexisting relationships with community partners, as well as with two longstanding community coalitions in its service area with complementary goals. The clinical champions at Heywood found the Roadmap to be a useful tool to identify critical stakeholders (e.g., local Area Agencies on Aging, assisted living facilities, telehealth organizations, APS partners, the Gardner Area Interagency Team members, and community physicians). Heywood then started reaching out to these stakeholders through community meetings and presentations to inform them about the ongoing elder mistreatment work at Heywood, generate discussion among stakeholders, and create a closer working relationship with APS.

Factors Affecting Toolkit Implementation

The COVID-19 outbreak saw declines in patients presenting in the ED and disrupted ED workflow. At Heywood and other participating EDs, EMED Toolkit implementation converged with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Heywood launched the EMED Toolkit in February 2020 and by March of that year, COVID cases had begun to inundate EDs across the country, including those in Massachusetts. The number of older adults presenting in the ED declined as their fears of infection with the coronavirus grew. Screening for elder mistreatment in the ED, however, did not abate at Heywood.

Heywood systems and functioning helped facilitate Toolkit adoption and implementation. Heywood has a rich history of community engagement. Because it is a relatively small hospital, clinical champions were able to obtain approvals quickly via uncomplicated decision-making channels. Hospital leadership, clinical champions, ED nursing staff, and Social Services staff each played critical roles in the successful implementation of the EMED Toolkit. The clinical champions set high goals for implementation and committed to achieving those goals, even with the unexpected demands of the COVID-19 pandemic. They reinforced the importance of the EM-EDAP and training to maximize completion rates and to create a streamlined workflow for staff to use the EM-SART. When workflow issues did arise, they were able to quickly troubleshoot and implement solutions.

Results of Implementation

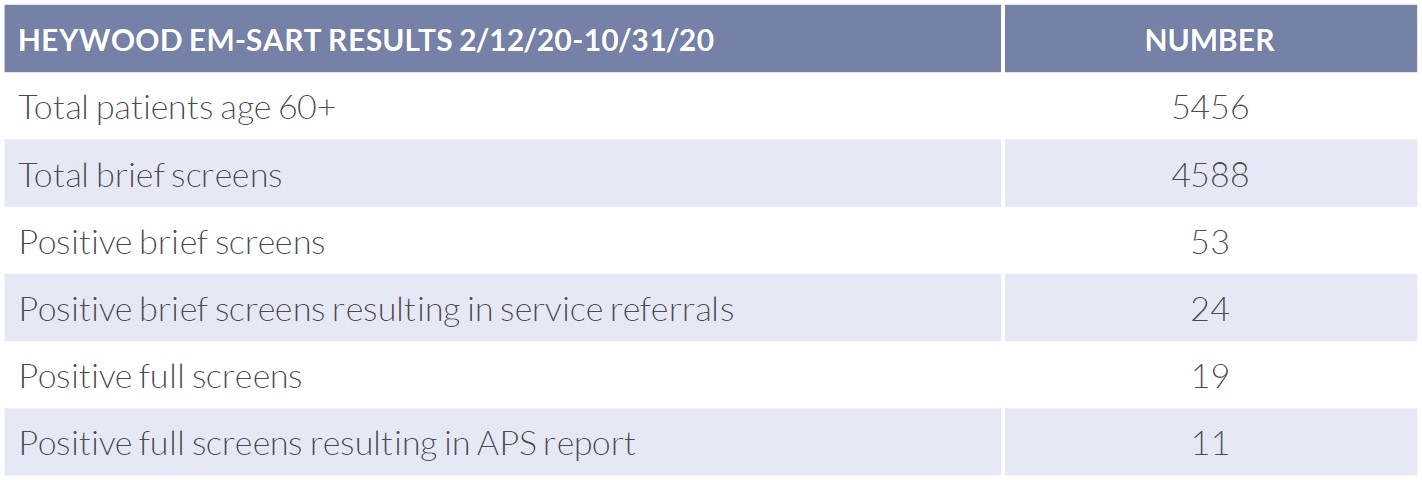

ED-based elder mistreatment screening, identification, and response increased from pre-implementation to implementation. The dedication of the ED staff and clinical champions to the EMED Toolkit and patients resulted in screening rates and case identification that vastly exceeded the two cases identified in the year prior to implementation. Over nine months, the ED used the EM-SART to screen 4,588 (84%) older ED patients. Of those, 53 received the full screen, resulting in 19 positive screens for possible mistreatment. Of these 19 patients, 11 were reported to APS, a more than seven-fold (annualized) increase over the prior year. Most of the remaining positive screens were handled by Heywood’s Social Services team, who connected the older adult to support in the community.

“Over time, it became second nature . . . and we’re able to kind of change the way that we looked at it more. So it definitely improved things.”

– ED staff member

ED-based elder mistreatment screening, identification, and response rates were sensitive to onset of COVID-19 protocols and workflow modifications. LBJ ED screening of older adults for elder mistreatment prior to EMED Toolkit implementation is unknown. During EMED Toolkit implementation, however, 1,218 brief screens (20% of ED patients aged 65 years or older) were completed, resulting in 23 positive brief screens and four full screens that prompted staff to submit reports to APS. In the four cases reported to APS, staff suspected that patients were experiencing psychological abuse, physical abuse, and neglect (physical and medical). In addition, one patient was believed to be experiencing financial exploitation in conjunction with another form of abuse. All four patients appeared to lack, or have limited access to, needed resources, and all presented with fractures, malnutrition, and dehydration. Based on the results of each full screen, staff instituted safety planning for three out of the four suspected cases. Missing full screen data for 19 of the positive brief screens may have affected the actual number of EM cases reported. Noticeable trends in both screening and positive screen rates correlated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (decreased brief screening rates), nursing staff taking over administration of both the brief and full screens (increased brief screening rates and decreased full screening rates), and inclusion of additional observational items on the brief screen (increased positive brief screen rates).

Heywood made no major modifications to the Toolkit. Heywood effectively integrated the EMED Toolkit into its usual ED care by incorporating the brief screen questions from the EM-SART into the EMR. Staff described the EM-SART as easy and practical to use because the algorithm guided them on what to do next and with whom to consult.

ED staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices improved. Staff responses on the EM-EDAP indicated an increased awareness of elder mistreatment and community resources over time. Initial EM-EDAP results indicated that staff members did not know how to properly report to or follow up with APS, were unaware of relevant resources in the community, and were doubtful about implementing a new screening protocol in the ED with their limited time and resources. Conversely, findings from the second EM-EDAP revealed that staff had gained confidence in their capabilities to address elder mistreatment as well as in reporting suspected cases of elder mistreatment to APS. Moreover, results from the second EM-EDAP indicated that a larger percentage of staff members felt confident in their ability to identify and address elder mistreatment. However, staff still reported levels of uncertainty regarding specialized community resources available for older adults at risk for elder mistreatment. Staff also reported barriers to practice such as navigating caregiver relationships and communication difficulties with older adult patients.

As noted earlier, prior to EMED Toolkit implementation, Heywood ED staff were mainly relying on the hospital’s Social Services Department to report cases of suspected elder mistreatment to APS, and were not kept informed about the outcomes of these reports. To address this issue, ED and Social Services staff established an internal feedback loop that strengthened the connection and increased trust between the two departments. Now, in addition to referring all patients screening positive on the full screen to Social Services, ED staff are also submitting reports of suspected elder mistreatment directly to APS, resulting in direct correspondence from APS to ED staff about these reports. Clinical champions are also developing processes to include APS correspondence and referral outcomes in patient records. With these new communication procedures, ED and Social Services staff are working as a collaborative, intraorganizational team to assess and manage cases.

Toolkit implementation did not disrupt ED functions. The training and new screening protocols did not have a significant effect on ED functioning during the implementation period compared to the pre-implementation period. Although the overall number of patients seen in the ED decreased during the implementation period, the percentage of older adults admitted increased (39% vs. 35%). Even so, both the mean and median length of stay for older adults decreased during the implementation period vs. the pre-implementation period. Thirty-day returns to the ED increased during implementation (22% vs. 19%) due to readmission spikes in April and August 2020. Although launching the EMED Toolkit took considerable effort, the clinical champions reported that staff were highly receptive to the training and the EM-SART. Because Heywood was committed to optimizing care for older adults, they were willing to address any implementation challenges, either on their own or by brainstorming with study staff. When ED staff implementing the EMED Toolkit brought up challenges or issues they were experiencing to the clinical champions, the clinical champions modified workflows to meet implementation goals. The clinical champions actively advocated for staff engagement with the EM-EDAP, offered training incentives for staff, responded to feedback on the EM-SART process, and used the Roadmap to establish internal processes to incorporate feedback from APS into patient records.

Key Lessons Learned

Heywood has taken significant steps to institutionalize the EMED Toolkit in their ED and in the surrounding community. Heywood continues to refine their practices according to local strengths and needs. ED staff has continued to use the EM-SART to screen for elder mistreatment despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and a change of leadership, when one clinical champion transferred from the ED to Infection Prevention & Control. Heywood has also begun using a new EMR system, and plans to incorporate the EM-SART into this system in the near future. Most important, EMED Toolkit implementation at Heywood has shown that:

- Small, rural hospitals can effectively implement the EMED Toolkit.

- Bedside nurses have a critical role to play in screening for elder mistreatment.

- Universal screening of older adults for elder mistreatment using a two-step process

is feasible in the ED. - Creating a feedback loop between the ED and Social Services strengthens

interorganizational communication and relationships. - While rural hospitals often lack specialized resources, their relative lack of red tape

can enable nimble initiation and implementation of novel approaches.

Still, during implementation, Heywood ED staff struggled with how to implement the brief screen with older adults who have an altered mental state—whether due to a treatable temporary condition such as a urinary tract infection, or a chronic condition such as dementia. Patients with an altered mental state have difficulty answering brief screen questions. After discussion with National Collaboratory members, Heywood’s ED continued to implement the brief screen with all older adult patients and proceed to the full screen based on brief screen results. However, the experience at Heywood has shown that further modifications to the EM-SART and/or training are needed for identifying mistreatment among older patients with altered mental states.

“Our relationship with Elder Protective Services was enhanced . . . We were able to effect change at a state level, at a local level, and within our hospital system by working on this project . . . [Elder Protective Services] will work with me now”

– ED staff member

Follow-up and the Future

Heywood entered the study with strong community connections relative to other study participants. Yet, discussions with Heywood staff and at community meetings show there is still a need to deepen the community’s understanding of elder mistreatment and the systems that can address it. Based on input from leaders at Heywood, the National Collaboratory has added content to the training to educate hospital staff on APS structure and processes. Ongoing discussions are needed to further develop community-based solutions that can increase education about elder mistreatment and promote communication among community stakeholders.

“The elder mistreatment program helped us to really stress the importance of the early identification, and Nursing was able to buy in. The medical staff actually started to buy in. Because they started to see the fruit of their labors and the opportunities that were perhaps missed years back.”

– ED staff member

About the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment and EDC

With funding from The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment was founded in 2016 with a charge to develop a scalable response to the prevalence of elder mistreatment. This group is comprised of national experts in elder mistreatment from the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and Joan & Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University, with Education Development Center (EDC) serving as the Collaboratory convener, EDC is a global nonprofit with more than 60 years experience designing, testing, and implementing innovative programs addressing critical challenges in health, education, and economic inequality.

To learn more: contact us at NCEAEM@edc.org or visit https://www.edc.org/national-collaboratory-address-elder-mistreatment