New Geriatric ED Accreditation – and why you should care

With Chris Carpenter

The way we currently provide geriatric emergency care is not sustainable. With the growing aging population, the dwindling medicare dollars, and the recognition that we need to improve the quality of geriatric care, we have to find ways to transform the systems in which we care for our older patients. Now there is a new step forward in this direction: EDs around the country can become accredited through ACEP as a Geriatric EDs (or geriatric-friendly ED) at three different levels. This accreditation is setting a new standard for geriatric care and for what it means to be a geriatric ED (GED). The accreditation is set up to work for any hospital from the smallest, rural ED, to a large, urban center with its own, separate GED space. Chris Carpenter, a major force behind the GED guidelines and accreditation, talks with me about why this is important, why you should care, and responds to potential criticisms and concerns.

Why geriatrics? America (& the World) Is Aging

Only 4% of Americans in 1900 were over the age of 65 compared with an anticipated 21% by 2050. Mid-20th Century medical leaders recognized an increasing sector of society with uniquely age-related health care demands and developed the specialty of geriatrics.1 By the 1980’s experts realized that the sheer number of Baby Boomers who would survive into old age would outstrip the availability of geriatricians.2 Even worse, so few physicians were choosing to enter the field of geriatrics in the United States that the ability of medical schools and residency to adequately expose trainees to the principles of healthy aging and evidence-based management of geriatric syndromes was increasingly inadequate.3

Older Adults in the ED: What Challenge?

Emergency Medicine is one of the youngest specialties in the House of Medicine. Research over the last 30 years of Emergency Medicine growth has highlighted some unpleasant realities about older adult emergency care. Aging adults more often present to the ED by ambulance, often require more time and labs and/or imaging, are admitted more often to intensive care, and still often view their experience of care far less favorably than do younger populations.4-7 ED nurses and physicians felt unprepared to effectively provide care for frail, often complex older adults,8,9 while opinion leaders intermittently highlighted the challenges (and opportunities) facing current and future emergency providers because of an aging population.10-14

Market Shares, Advertising Geriatrics, and Ensuring Quality

Acknowledging that solutions required a multi-pronged approach based upon research evidence whenever such evidence existed, the first generation of emergency medicine advocates for aging adults collaborated with the American Geriatrics Society (AGS), Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM), and the National Institute of Aging to identify and describe the highest priority research questions upon which funders and investigators ought to focus.15-17 Concurrently, quality indicators were developed, representing the minimal standard to which any ED (rural or urban, academic or community) should be able to attain.18 The American Board of Emergency Medicine and Council of Residency Directors also identified geriatric core competencies that every emergency medicine residency graduate must demonstrate, which were then added to in-service and certification exams.19 Prioritizing research, clinical protocols, and educational objectives was associated with increasing understanding about challenges confronting efficient care for aging adults, such as recognizing dementia and delirium, measuring frailty, and predicting future falls.20 Hospital leaders began to recognize an opportunity to increase market share and 30 “Geriatric EDs” opened in the United States between 2009 and 2013.21

Style vs. Substance: Guidelines and Accreditation

Unfortunately, many of the early self-defined “Geriatric EDs” demonstrated very little identifiable qualities to distinguish them from any other ED.21 In 2013, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), SAEM, and AGS joined with the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) to develop and publish the “Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines” that were subsequently endorsed by the Boards of Directors of all four organizations and then by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians.22-24 These guidelines, which were designed to “geriatricize” every adult ED rather than to advocate for separate emergency space for older adult care, provide explicit descriptions of the staffing, continued staff training, protocols, infrastructure, and quality indicators that define and distinguish older adult models of care from emergency care for other populations.25

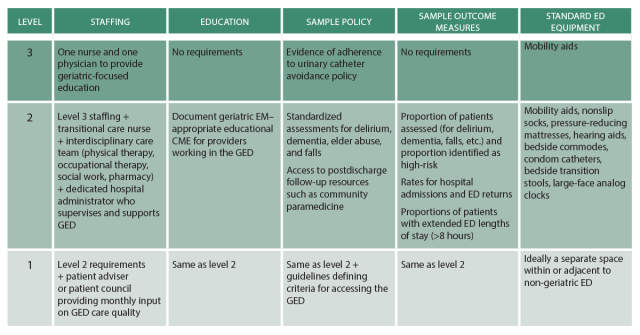

Publishing – whether research, theories, essays, or guidelines – is an inadequate strategy when used alone to motivate healthcare change. In fact, the Institute of Medicine estimates that incorporating research into bedside practice requires on average 17 years for 14% of evidence.26 Current projections estimate that Medicare will be bankrupt by 2028, so society probably does not have several decades to await the diffusion of innovation. In 2017 the ACEP Board of Directors approved a proposal to accredit EDs on a three-tier system based on demonstrable adherence to the GED Guidelines. Accreditation will occur every 2-3 years and use a tiered approach (similar to trauma centers) to be adaptable to the unique resource capability and patient care needs of each hospital, from the small rural ED to the large academic mega-center (Table).27

Three Levels of Accreditation

For Sample Criteria for ACEP Geriatric Emergency Accreditation see the table in the ACEP Now article. The table is reproduced below.

© 2011- 2016, American College of Emergency Physicians. Reprinted with Permission

© 2011- 2016, American College of Emergency Physicians. Reprinted with Permission

Geriatrics and Emergency Medicine – The Con Perspectives

Many logical arguments can be made in response to the GED Guidelines and new ACEP accreditation process. Healthy skepticism is….healthy, anticipated, and needed to polish advocates’ passionate ideas. Common criticisms for “geriatricizing” EDs exist and include:

- “The average emergency medicine provider manages multiple geriatric patients every shift. We know what we are doing and don’t need any guidelines or education.” RESPONSE: Despite quality indicators,18,28,29 residency core competencies,19 and guidelines,22 contemporary ED providers continue to miss more cases of dementia30and delirium31-33 than they identify and fall victims rarely receive guideline-directed care.34 On a specialty-wide level, there is measurable room for improvement.

- “Where is the evidence that GEDs improve the cost or outcomes of emergency care?” RESPONSE: Obviously, adapting emergency medicine for an aging population should be built on the best available evidence and demonstrate improved outcomes, not simply different processes that we assume must improve some or all aspects of the Triple Aim (improved well-being and health with a better healthcare experience at the same or lesser cost). Initial research around EDs that have adapted for an aging population demonstrate reduced admission rates but no changes in ED returns or hospital length of stay.35 Other studies indicate that efforts to improve the detection of vulnerable older adults in ED settings actually increase short-term use of referrals and outpatient resources with the benefit of decreased functional decline.36 Undoubtedly, the evidence is sparse and hardly convincing, but the bulk of the evidence indicates that the status quo is grossly inadequate, so if the Guidelines and accreditation are not the correct response, what is the alternative? Additionally, skeptics should consider whether earlier studies evaluated the most patient-centric outcomes to evaluate effectiveness.37 Should the outcomes of interest be hospital-focused (ED returns, admission rates, length of stay) or patient-focused (functional decline, maintenance of independence, quality of life)?

- “Accreditation just seems like another hoop to jump through and another revenue source for somebody. Is there any evidence that accreditation for anything (pediatrics, stroke care, cardiac emergencies, trauma) improves any aspect of medical care?” RESPONSE: Accreditation is expensive and often an onerous distraction away from the mission of providing daily healthcare. Nonetheless, ACEP has already decided to pursue this course as one strategy to promote widespread implementation of principles from the GED Guidelines. Trauma center accreditation usually occurs at the state level and the majority use verification processes and criteria from the American College of Surgeons. On the other hand, stroke centers are certified by the Joint Commission and chest pain centers by the Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care.38,39 Stroke and chest pain accreditation only began in 2002 and 2003, respectively, so evidence linking credentialing to outcomes is limited.21 However, stroke center care has been associated with better outcomes,40 as has been the case for trauma care at higher level centers.41,42 The onus is on ACEP and the geriatric EM accreditation team to minimize the requisite workload for hospitals to optimize the balance between meaningful accreditation that links evidence-based quality with patient outcomes and credentialing.

- “Emergency medicine was founded on the principle of anything for anyone at any time. Fragmentation of EDs into geriatrics, pediatrics, cardiac and stroke centers of excellence is a step backwards for our specialty.” RESPONSE: Fragmentation of care is neither desirable nor the intent of the accreditation process. Instead, the vision is that an older adult presenting to an ED anywhere across the nation receives the same high-level care that incorporates the uniqueness of geriatric emergencies.43 The ACEP accreditation process was cognizant that rural EDs have differing access to consultants then urban academic centers, so a leader from the ACEP Rural EM section was included in preparing the recommendations.27

- “Almost all of the GED recommendations would appear appealing to emergency patients of all ages. Why focus on geriatrics”? RESPONSE: Undoubtedly, many attributes of the geriatric ED will benefit younger populations in terms of comfort, rapid recognition of incident delirium, appropriate considerations of palliative care, and a focus on measurable patient-centric outcomes. However, the reverse is less likely to hold true. Older adults exhibit unique age-related vulnerabilities that too often remain underappreciated without focused training and a sustained awareness. Two decades of emergency medicine research repeatedly demonstrate suboptimal, often abysmal detection of dementia,30 delirium,31-33 future fall risk,34 and polypharmacy while guidelines and educational resources have failed to significantly improve this situation. The demographic imperative of an aging society combined with almost 30 years of emergency medicine experience constitute the rationale for the focus on geriatrics.44

Choose Wisely and Choose Quickly

ACEP is pursuing accreditation of EDs based on the demonstrable delivery of geriatric care highlighted by the GED Guidelines. Choosing not to participate is an option, but an aging society and looming Medicare bankruptcy mean that if emergency medicine does not steer the ship away from the brink others will grab the wheel – and the values of “others” are unlikely to align with the perspectives of frontline emergency providers. Blind acceptance of the recommendations is not warranted or required, but participation in the process to meet the needs of patients, families, providers, and societal responsibilities for stewardship is essential.

References

- Geriatrics–the care of the aged. JAMA 2014;312:1159.

- Reuben DB, Bradley TB, Zwanziger J, et al. The critical shortage of geriatrics faculty. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:560-9.

- Reuben DB, Bradley TB, Zwanziger J, Beck JC. Projecting the need for physicians to care for older persons: effects of changes in demography, utilization patterns, and physician productivity. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:1033-8.

- Singal BM, Hedges JR, Rousseau EW, et al. Geriatric patient emergency visits. Part I: Comparison of visits by geriatric and younger patients. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:802-7.

- Hedges JR, Singal BM, Rousseau EW, et al. Geriatric patient emergency visits. Part II: Perceptions of visits by geriatric and younger patients. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:808-13.

- Strange GR, Chen EH. Use of emergency departments by elder patients: a five-year follow-up study. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:1157-62.

- Baraff LJ, Bernstein E, Bradley K, et al. Perceptions of emergency care by the elderly: results of multicenter focus group interviews. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:814-8.

- Roethler C, Adelman T, Parsons V. Assessing emergency nurses’ geriatric knowledge and perceptions of their geriatric care. J Emerg Nurs 2011;37:132-7.

- Snider T, Melady D, Costa AP. A national survey of Canadian emergency medicine residents’ comfort with geriatric emergency medicine. CJEM 2017;19:9-17.

- Sanders AB, Morley JE. The older person and the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:880-2.

- Adams JG, Gerson LW. A new model for emergency care of geriatric patients. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:271-4.

- Schumacher JG. Emergency Medicine and Older Adults: Continuing Challenges and Opportunities. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23:556-60.

- Wilber ST, Gerson LW, Terrell KM, et al. Geriatric emergency medicine and the 2006 Institute of Medicine reports from the Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the U.S. Health System. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:1345-51.

- Hwang U, Morrison RS. The geriatric emergency department. J Am Geratr Soc 2007;55:1873-6.

- Carpenter CR, Gerson L. Geriatric emergency medicine. In: LoCicero J, Rosenthal RA, Katic M, Pompei P, eds. A Supplment to New Frontiers in Geriatrics Research: An Agenda for Surgical and Related Medical Specialties. 2nd ed. New York: The American Geriatrics Society; 2008:45-71.

- Carpenter CR, Shah MN, Hustey FM, Heard K, Miller DK. High yield research opportunities in geriatric emergency medicine research: prehospital care, delirium, adverse drug events, and falls. J Gerontol Med Sci 2011;66:775-83.

- Carpenter CR, Heard K, Wilber ST, et al. Research priorities for high-quality geriatric emergency care: medication management, screening, and prevention and functional assessment. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:644-54.

- Terrell KM, Hustey FM, Hwang U, Gerson LW, Wenger NS. Quality indicators for geriatric emergency care. Acad Emerg Med 2009 16:441-9.

- Hogan TM, Losman ED, Carpenter CR, et al. Development of geriatric competencies for emergency medicine residents using an expert consensus process. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:316-24.

- Carpenter CR, Rosenberg M, Christensen M. Geriatric emergency medicine guidelines for staffing, training, protocols, infrastructure, and quality improvement. Emerg Med Reports 2014;35:1-12.

- Hogan TM, Olade TO, Carpenter CR. A profile of acute care in an aging America: snowball sample identification and characterization of United States geriatric emergency departments in 2013. Acad Emerg Med 2014 21:337-46.

- Rosenberg M, Carpenter CR, Bromley M, et al. Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63:e7-e25.

- Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal Older Adult Emergency Care: Introducing Multidisciplinary Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1360-3.

- Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal Older Adult Emergency Care: Introducing Multidisciplinary Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2014 21:806-9.

- Hwang U, Carpenter CR. The Geriatric Emergency Department. In: Wiler JL, Pines JM, Ward MJ, eds. Value and Quality Innovations in Acute and Emergency Care. Cambridge UK: Cambridge Medicine; 2017:82-90.

- Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient-Centered Systems. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer; 2000:65-70.

- ACEP Accredits Geriatric Emergency Care for Emergency Departments. American College of Emergency Physicians, 2017 (Accessed April 10, 2017, at http://www.acepnow.com/article/acep-accredits-geriatric-emergency-care-emergency-departments/.)

- Schnitker LM, Martin-Khan M, Burkette E, Beattie ER, Jones RN, Gray LC. Process quality indicators targeting cognitive impairment to support quality of care for older people with cognitive impairment in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:285-98.

- Schnitker LM, Martin-Khan M, Burkett E, et al. Structural quality indicators to support quality of care for older people with cognitive impairment in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:273-84.

- Carpenter CR, DesPain B, Keeling TK, Shah M, Rothenberger M. The Six-Item Screener and AD8 for the detection of cognitive impairment in geriatric emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:653-61.

- Lewis LM, Miller DK, Morley JE, Nork MJ, Lasater LC. Unrecognized delirium in ED geriatric patients. Am J Emerg Med 1995;13:142-5.

- Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:248-53.

- Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:193-200.

- Tirrell G, Sri-on J, Lipsitz LA, Camargo CA, Kabrhel C, Liu SW. Evaluation of older adult patients with falls in the emergency department: discordance with national guidelines. Acad Emerg Med 2015 22:461-7.

- Keyes DC, Singal B, Kropf CW, Fisk A. Impact of a New Senior Emergency Department on Emergency Department Recidivism, Rate of Hospital Admission, and Hospital Length of Stay. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63:517-24.

- McCusker J, Verdon J, Tousignant P, de Courval LP, Dendukuri N, Belzile E. Rapid Emergency Department Intervention for Older People Reduces Risk of Functional Decline: Results of a Multicenter Randomized Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1272-81.

- Platts-Mills TF, Glickman SW. Measuring the Value of a Senior Emergency Department: Making Sense of Health Outcomes and Health Costs. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63:525-7.

- Advanced Certification for Primary Stroke Centers. The Joint Commission, 2015. (Accessed May 22, 2017, at http://www.jointcommission.org/certification/primary_stroke_centers.aspx.)

- Chest Pain Center Accreditation. Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, 2015. (Accessed May 22, 2017, at http://www.scpcp.org/services/cpc.aspx.)

- Rajamani K, Millis S, Watson S, et al. Thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in Joint Commission-certified and -noncertified hospitals in Michigan. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:49-54.

- Cudnik MT, Newgard CD, Sayre MR, Steinberg SM. Level I versus Level II trauma centers: an outcomes-based assessment. J Trauma 2009;66:1321-6.

- Haas B, Stukel TA, Gomez D, et al. The mortality benefit of direct trauma center transport in a regional trauma system: a population-based analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:1510-7.

- Carpenter CR, Platts-Mills TF. Evolving prehospital, emergency department, and “inpatient” management models for geriatric emergencies. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29:31-47.

- Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff 2013;32:2116-21.

Image credit [1]

Music credit: Bob Dylan, The Times They Are Changing, Columbia Records, 1964

This entry was posted in Systems and Administration. Bookmark the permalink.

Hosted by

Dr. Christina Shenvi is an associate professor of Emergency Medicine at the University of North Carolina. She is fellowship-trained in Geriatric Emergency Medicine and is the founder of GEMCast. She is the director of the UNC Office of Academic Excellence, president of the Association of Professional Women in Medical Sciences, co-directs the ACEP/CORD Teaching Fellowship, is on the Annals of EM editorial board, is on the Geriatric ED Accreditation board of governors, and she teaches and writes about time management at timeforyourlife.org.