As avid readers of Regs & Eggs, you all know that one major area I have focused on has been the movement in our health care system away from fee-for-service payment towards more value-based care. Specifically, I have tried to keep you all up-to-date on the work of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS’) Innovation Center (“CMMI”) and the progress (or lack thereof) CMMI and private payors have made implementing the Acute Unscheduled Care Model (AUCM)—the emergency medicine-specific alternative payment model (APM) that ACEP developed. I also recently described a new effort from the American Medical Association (AMA) to create an APM in which different specialists, including emergency physicians, could possibly participate.

However, I feel it’s critically important to take a step back and make sure that you all as emergency physicians have an understanding of value-based care. What does value-based care truly mean? How will it affect you and your patients? We won’t truly move to a more value-based system unless emergency medicine is fully engaged in this effort—and I want to explore how we get there!

That is why I’m excited to announce that I’ve teamed up with the Geriatric Emergency Department Collaborative (GEDC), as well as West Health and the John A Hartford Foundation, to work on a series of blogs to take a dive deep into the concept of value-based care in emergency medicine. Our blogs will mainly focus on geriatric care principles—but the value-based care tenets we will explore are broadly applicable to other populations as well. As an added bonus, since I’m working together with GEDC, the blog series won’t only include my insights on the subject, but also the perspectives of numerous experts across the country.

So, without further ado, let’s get started! In this first blog, I’ve partnered with Dr. Kevin Biese, an emergency physician and leader at the forefront of connecting value-based care to geriatric emergency medicine, along with Megan Donovan, MBA, an independent management consultant and expert in the value of geriatric emergency departments to value-based care organizations.

As the title suggests, we want to provide a general overview of value-based care in emergency medicine. While doing so, we will also explore an approach of structuring and delivering emergency care for the geriatric population that is already in place and that has already proven to improve quality and reduce health care costs: geriatric emergency departments.

Value-based Care: What does it truly mean?

Value-based care (VBC) is a health care delivery and payment approach in which health care systems are incentivized to provide quality care at lower costs. Oftentimes, VBC delivery occurs within a clinically integrated network (CIN), which is an exclusive partnership of physicians that collaborate and partner (sometimes with or without hospitals) to deliver evidenced-based care and improve the quality of care for certain patient populations.

Rather than being compensated per billable intervention, as in a fee-for-service model (FFS), in VBC contracts, the healthcare system or CIN of physicians receive additional compensation for achieving high quality metrics at lower overall cost. VBC payment models are meant to encourage more preventive care, reduce re-hospitalizations, and incentivize more efficient care delivery models. Quality metrics are meant to ensure that good clinical care and patient outcomes are not sacrificed in the drive for higher efficiency.

Value-based care models are typically implemented through risk-based contracts. A risk-based contract places a greater responsibility on providers to provide high quality care at a lower cost. Every year, an increasing number of contracts are risk-based, meaning health care systems will not just receive bonuses for high value care, but will receive penalties for low value care.

There are many types of VBC contracts, including Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and other Advanced Payment Models (APMs). The largest ACO initiative is the national Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), which was created by the Affordable Care Act. Traditional ACO models, like the MSSP, often operate within an FFS system, but have bonuses for high value care at the end of the year. However, as CMS attempts to shift the healthcare system slowly away from FFS and towards VBC, CMMI just announced a new ACO model, called the ACO Reach model, which drives towards total capitation.

Capitation is a payment approach in which physicians are paid a fixed amount or flat rate to care for a patient during a specified period of time. In this type of approach, clinicians perhaps are even more highly incentivized to reduce costs since they are restricted by a confined budget.

Why should Emergency Medicine physicians care about the move towards value-base care?

Here are some of the main reasons you as emergency physicians should be involved in this movement towards value-based care. To sum it all up, as Wayne Gretzky said, you have to skate to where the puck is going…

- As part of CMMI’s new strategic vision, the Center announced that all Medicare beneficiaries will be in “a care relationship with accountability for quality and total cost of care” (i.e., tied to APMs or other VBC arrangements) by 2030. The percentage of our patients participating in an APM or a VBC arrangement will grow steadily over the next decade. Oftentimes, this means our patients have access to a wider array of support services offered by those APMs or VBC arrangements. We must view APMs and VBCs as an additional resource at our disposal to aid us in delivering high-quality care to our patients.

- In-patient hospital care is about one-third of total healthcare spend in this country. As health care systems are increasingly on the hook for high value care, they will become increasingly strategic about who is admitted to the hospital.

- The majority of patients (and over 60 percent of adults aged 65 and greater) are admitted to the hospital through the emergency department (ED). Health care systems cannot get a handle on health care spend without engaging the ED.

- Safely discharging frail patients requires increased work by the ED team.

EDs need to care about VBC arrangements because emergency physicians and the systems in which you practice are going to be under increasing pressure to safely transition patients home that might not medically need hospital admission. You need support and resources to do this well.

Geriatric EDs: A lynchpin connecting emergency care to value-based care

Similar to the concept of pediatric emergency departments, geriatric emergency departments (GEDs) incorporate specially trained staff, assess older patients in a more comprehensive way, and take steps to make sure the patient experience is more comfortable and less intimidating for older adults. All of this allows for a better care experience for older adults while in the ED and safer transitions to a community setting for those who do not need medical admission.

A GED has four key areas of differentiation from a traditional ED. First, physicians and nurses receive additional education in geriatric emergency medicine that provides added expertise in the emergency care of older adults. Additional education focuses on:

- Geriatric specific syndromes and concepts (e.g., atypical presentation of disease, changes with age, transitions of care) relevant to emergency medicine,

- Clinical issues nearly exclusive to geriatric patients (e.g., end of life care, dementia, delirium, systems of care for older adults), and

- Issues common to all ED patients but focused on the unique factors found in older adults (e.g., trauma in older adults, cardiac arrest care for the geriatric patient).

Second, GEDs have enhanced screening processes. Patients receive additional screenings that can quickly uncover physical or mental health risks that are more common in older adults. For example, screening tools uncover geriatric syndromes (like falls, polypharmacy, delirium, dementia) as well as social vulnerabilities (like food scarcity or elder mistreatment).

Third, GEDs are often supported by interdisciplinary team members that help provide enhanced community connections for the most vulnerable older adults, as well as focus on transitions of care. Team members can reach out to the local agency on aging, services like Meals on Wheels, physical therapy providers and home health agencies, or help facilitate direct to skilled nursing facility (SNF) transfers when an in-patient admission is not required.

Finally, a GED is usually not a separate space or standalone ED, but rather has structural enhancements to the physical environment that make the experience more conducive to older adults. Oftentimes this includes a designated, quieter, cordoned-off space within an ED, light dimmers, non-stick flooring to minimize falls, comfortable space for caregivers in the ED, or the inclusion of handrails.

In summary, the goals of GEDs are to improve transitions of care, avoid unhelpful hospital admissions or readmissions, identify unmet needs, and improve care quality and the patient experience. GEDs do this through the use of transitional care nurses or social workers by:

- Identifying underlying geriatric syndromes and social vulnerabilities through enhanced screenings

- Intervening upon findings

- Connecting to social services

- If appropriate and feasible, transitioning to home or community-based settings (hospital at home, primary care provider, etc.)

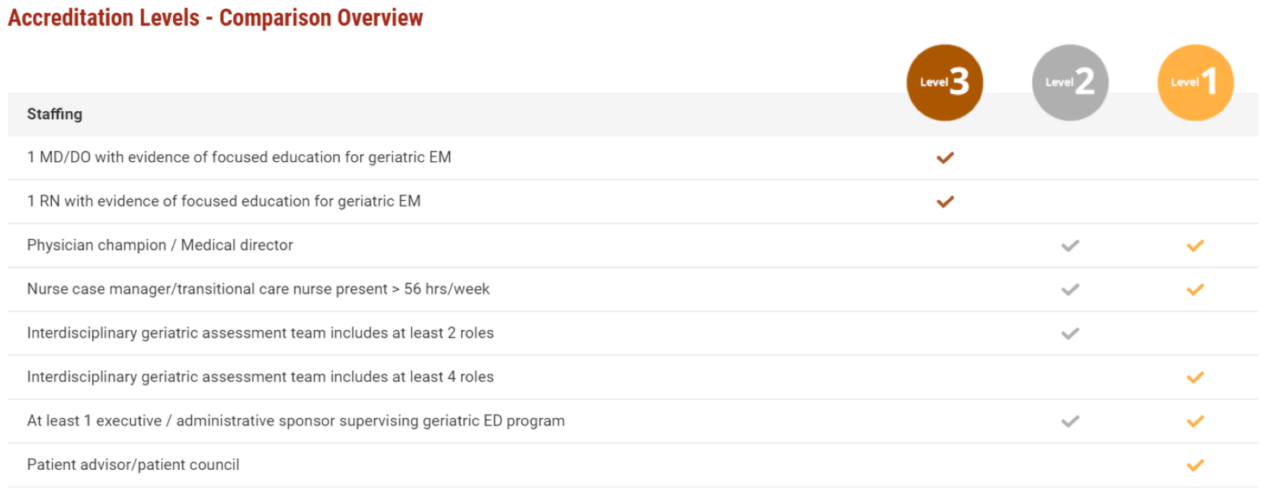

Though research in improving emergency care for older adults has been underway for decades, wide-scale adoption of geriatric emergency medicine care processes is relatively new. In 2013, the Geriatric ED Guidelines were created. In 2018, ACEP launched the Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation program, which established criteria for three levels of GED accreditation. There are now over 300 GEDs in the US, along with a growing presence internationally.

Exhibit 1: Three levels of geriatric emergency department accreditation

There is a growing body of literature that supports the outcomes of GEDs to lower cost, improve quality, and improve the patient experience:

- Up to 16.5 percent reduced risk of hospital admission2 and 17.3 percent of readmission3

- Up to $3,202 savings per Medicare beneficiary after 60 days4

- Decreased odds of 30- and 60-day fall-related ED revisit with PT services5

- 3 percent satisfaction with the clarity of discharge information and perceived wellbeing6

- Multiple studies showcasing improved experience across a variety of interventions7

GEDs are a proven example of emergency medicine facilitating higher value care for complex patients. They decrease the risk of unnecessary hospital admissions, improve patient experience in the ED and care transitions to the community, and decrease the need for repeat ED visits and re-hospitalizations by addressing the underlying risk factors (such as falls risks, polypharmacy, elder abuse, care giver fatigue, etc.) that may have precipitated the ED visit in the first place. EDs need to lead the charge to value-based care (and be supported for doing so), and GEDs demonstrate how this is possible.

Now that you all (hopefully) have a better understanding of the general concept of value-based care in emergency medicine and how GEDs already fit into the value paradigm, I want to give you a preview of what’s next. Future blogs in the series will explore how you as an emergency physician can participate in value-based initiatives. Not only will we look at what options currently exist for emergency physicians, but we will also examine how emergency medicine needs to evolve and change in order for you to better take advantage of these opportunities. Further, we will provide specific recommendations and tools you can use to negotiate value-based contracts or collaborate with value-based entities, like ACOs. Finally, we will discuss how emergency medicine can be provided beyond the four walls of the ED to drive value and truly meet the needs of patients.

We hope to publish the remaining blogs in the blog series over the next several months. In the meantime, rest assured, you will still get your weekly filling of regs and eggs on other regulatory issues affecting you and your patients!

Until next week, this is Jeffrey saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs!

Cited Sources

- Gonzalez Morganti, Kristy, Sebastian Bauhoff, Janice C. Blanchard, Mahshid Abir, Neema Iyer, Alexandria Smith, Joseph Vesely, Edward N. Okeke, and Arthur L. Kellermann, The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2013. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR280.html. Also available in print form.

- Hwang, U., Dresden, S.M., Rosenberg, M.S., Garrido, M.M., Loo, G., Sze, J., Gravenor, S., Courtney, D.M., Kang, R., Zhu, C.W., Vargas-Torres, C., Grudzen, C.R., Richardson, L.D. and (2018), Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations: Transitional Care Nurses and Hospital Use. J Am Geriatr Soc, 66: 459-466. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15235

- Dresden SM, Hwang U, Garrido MM, Sze J, Kang R, Vargas-Torres C, Courtney DM, Loo G, Rosenberg M, Richardson L. Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations: The Impact of Transitional Care Nurses on 30-day Readmissions for Older Adults. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Jan;27(1):43-53. doi: 10.1111/acem.13880. Epub 2019 Dec 1. PMID: 31663245.

- Hwang U, Dresden SM, Vargas-Torres C, et al. Association of a Geriatric Emergency Department Innovation Program With Cost Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e2037334. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37334

- Lesser A, Israni J, Kent T, Ko KJ. Association Between Physical Therapy in the Emergency Department and Emergency Department Revisits for Older Adult Fallers: A Nationally Representative Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2205-2212. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15469. Epub 2018 Aug 21. PMID: 30132800.

- Guttman A, Afilalo M, Guttman R, Colacone A, Robitaille C, Lang E, Rosenthal S. An emergency department-based nurse discharge coordinator for elder patients: does it make a difference? Acad Emerg Med. 2004 Dec;11(12):1318-27. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.07.006. Erratum in: Acad Emerg Med.2005 Jan;12(1):12. PMID: 15576523.

- Berning MJ, Oliveira J E Silva L, Suarez NE, Walker LE, Erwin P, Carpenter CR, Bellolio F. Interventions to improve older adults’ Emergency Department patient experience: A systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Jun;38(6):1257-1269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.012. Epub 2020 Mar 12. PMID: 32222314.

Faculty