Patient Scenario

Mrs. C is a 72-year-old woman who had been coughing with an intermittent fever for six days when she came to her community emergency department (ED). Her past medical history was significant for active cigarette smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. Her medications at baseline included simvastatin, lisinopril, and an albuterol metered dose inhaler, and she managed daily self-care at her home. She had spent the past 2 days sitting on the couch. Mrs. C was anxious about going to the ED during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also worried she was too weak to get in and out of the shower alone. In the ED, her vital signs were HR= 101, BP= 146/85, RR= 20, T= 98.9°F, O2 Sat= 93% on room air, 98% on 2 liters nasal cannula. Her chest X-ray was notable for a patchy infiltrate of her right lower lobe. A diagnostic nasopharyngeal molecular swab was sent for COVID-19 testing and results were pending. Hospital admission was advised. Mrs. C refused because she needed to take care of her dog at home. “I’m not staying in the hospital tonight,” she told the ED nurse. Mrs. C had decision-making capacity and discussed the benefits and risks of leaving the ED with the provider.

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed deep problems in the way we care for medically complex older adults.However, it has also accelerated opportunities to support and keep these individuals safely in their homes both during the pandemic and in the future. Mrs. C’s situation represents the common ED dilemma of an independently living, medically complex older person with declining health who doesn’t necessarily require hospitalization. Many ED providers would admit Mrs. C to the hospital, potentially increasing her risk for COVID-19 or other nosocomial infection and filling a bed potentially needed by a sicker patient. Alternatively, she might be sent home alone, but risk returning to the ED quickly. However, there is a third option, where providers could ensure Mrs. C’s safe transition back home by discussing her goals and preferences, assessing her medical and social needs, identifying gaps, and arranging in-home services right from the ED. We propose that by investing in transitional care coordination encompassing comprehensive assessments, onsite case management and referrals to health and social services at home, EDs can meet the medical and social needs and the preferences of patients like Mrs. C.

Home and Community-Based Supports: Matching Patient Needs to the Appropriate Level of Care

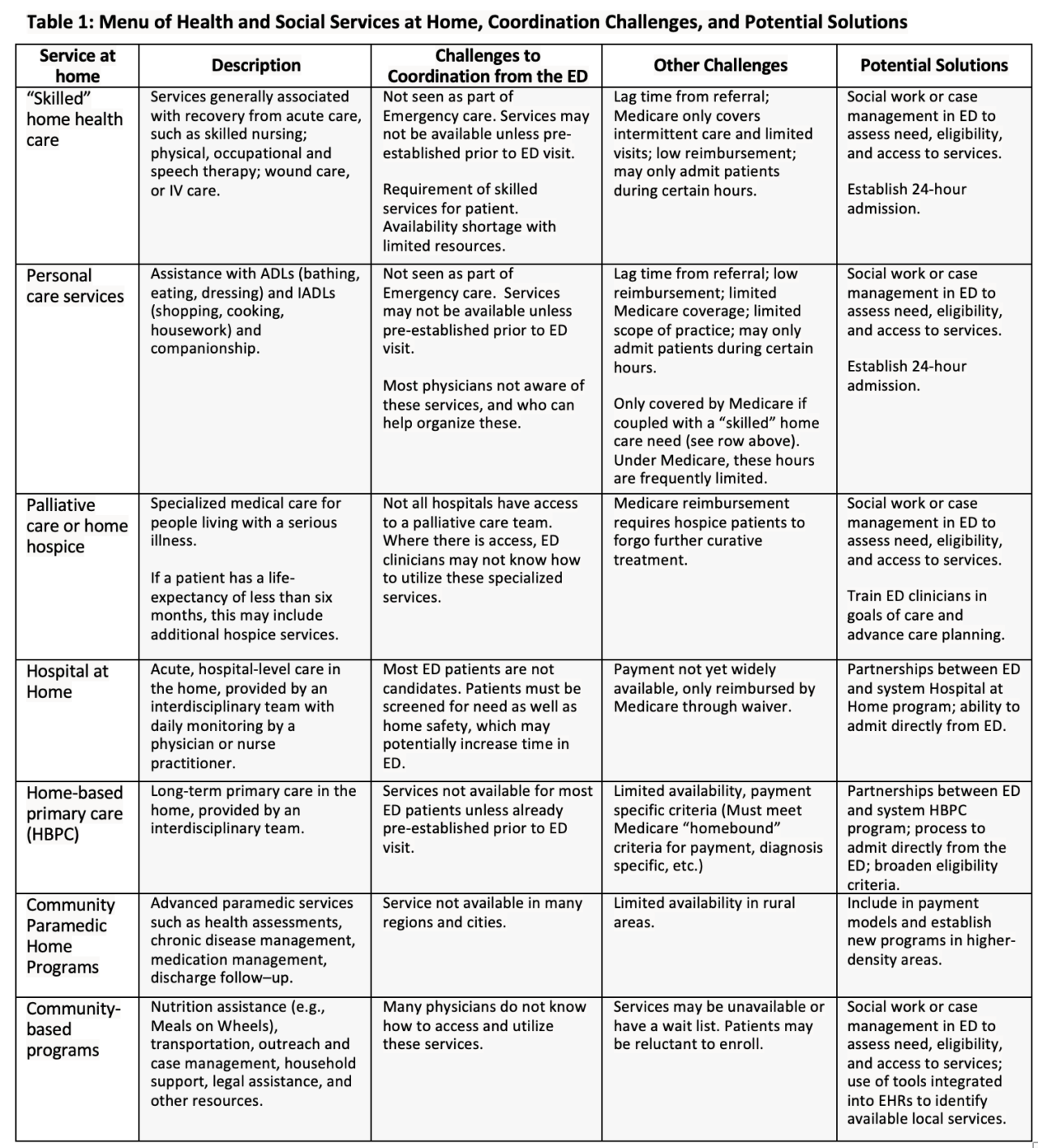

There is a broad range of medical, community, and social services to help patients like Mrs. C in the home. But until recently, home health and community-based programs have been underutilized by ED providers. This may be because providers either do not know what services are available or lack pathways to access them. Many of these services are covered by Medicare if there is a medical need. Some services are offered through community-based organizations. Importantly, in most cases social workers or care coordinators can potentially connect patients to these services directly from the ED.

Home health care offers therapeutic and some non-therapeutic services, often after acute events such as a joint replacement. Services may include skilled nursing, physical, occupational and speech therapy, and wound care. Home health services may also include aides to assist with daily activities like cooking, feeding, bathing, dressing, safely moving about the home, taking medications, and providing companionship. While Medicare covers some home health care services, long-term personal care services are generally paid through Medicaid or private pay.1

For routine medical care, patients with complex medical conditions who are homebound or have difficulty getting to a doctor’s office may benefit from home-based primary care (HBPC).2 In these “house call” programs, an interdisciplinary team manages patients’ care needs on a long-term basis, with regular in-home visits from medical providers. Another emerging model of home-based medical care is the Veterans Health Administration’s medical foster home program, where up to three individuals may live in the home of a trained caregiver supported by a home-based primary care team.3

For higher levels of care, Hospital at Home programs are an innovative model that is increasingly available.4 This home admission option provides acute care (for instance, infusion services) that can allow patients to return home from the hospital sooner or avoid a hospital stay altogether with daily monitoring. And, for patients living with a serious illness, home-based palliative and hospice care can provide specialized medical care focused on quality of life.5

Finally, community-based services also play an important role in home support. In a growing number of areas, community paramedics are partnering with health systems and community-based programs to deliver and set up equipment like pulse oximeters and home monitoring devices.6 They also assist with chronic care management, medication administration, and post-discharge visits. Other community-based programs may provide support such as Meals on Wheels, transportation, outreach and counseling, and other services to older adults.

The Changing Role of the Ed: Building Transitional Care Capacity

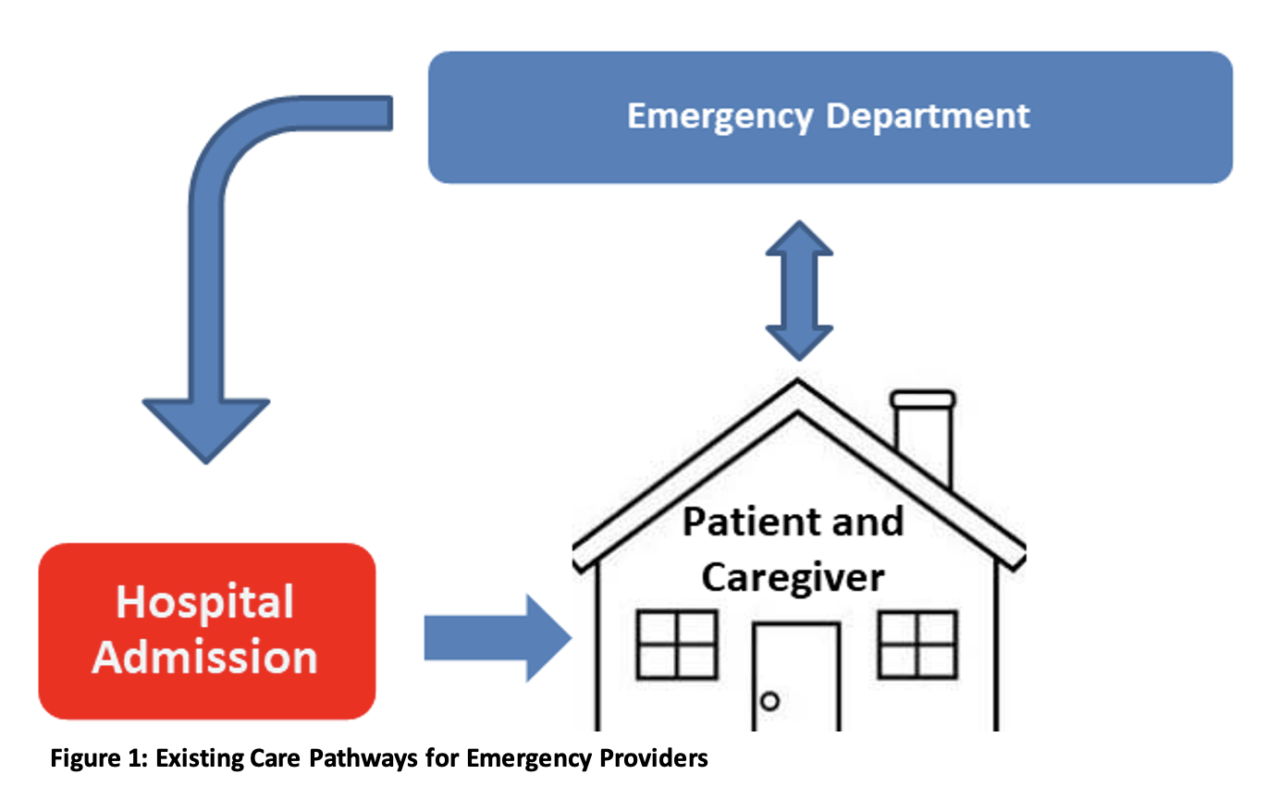

EDs have traditionally served as the health care safety net for acute medical care needs, providing health care to underserved and disenfranchised populations.7 In the past decade, the role of the ED has expanded. EDs now provide many ambulatory-type services. Primary care practices increasingly refer patients to the ED for “complex diagnostic workups.”8 ED encounters are often sentinel events unmasking unmet social and functional needs that can be addressed with the home delivery of social and medical services. But in EDs lacking the staffing and assessment tools to access and establish potential home supports and medical care, patients are often admitted for failure to thrive (or the infamous “social admission”). (See Figure 1.)

This decision may conflict with patient preferences and fill needed hospital beds.

EDs can build capacity to support outpatient transitions of care by putting systems in place to:

- assess patient risk and determine appropriate types of discharge.

- identify appropriate and available community-based services.

- enroll patients directly in these programs.

Assessment tools like the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) can help identify older patients who risk experiencing adverse health outcomes and need support. Many EDs have already integrated the ISAR tool with case management and social service interventions to improve successful transitions back home.9 Programs such as NowPow, which is integrated into the EPIC electronic medical record system, can help assess patients’ home environments, identifying unmet social needs and linking patients with nearby community resources.10 EDs may also consider developing their own decision support tools to determine whether a patient can be safely discharged home with assistance. These tools take into account factors such as the frequency of a patient’s ED visits, the time and date of the visit in relation to service availability (as some programs may not be able to enroll new patients at night or on weekends), and resources available at home, including food, medications, and family or other caregivers.

Adequate staffing is perhaps the most daunting challenge in supporting safe outpatient transitions to home. Many EDs lack discharge planners with established processes of contacting and coordinating community-based care. While some EDs have a case manager or a social worker who can assist in engaging these services, they may only be available on certain days or hours. Dedicated case management staffing is a worthwhile and necessary investment for EDs to meet quality goals of safety, timeliness, patient-centeredness, efficiency, effectiveness, and ensuring access for all older adults to patient care.11 Geriatric Emergency Departments (GEDs), which have emerged to address the special care needs of older patients, can serve as a model. Embedded case managers are so essential to this model that the highest level of GED accreditation through the American College of Emergency Physicians requires 56 hours of such ED coverage per week.12 These nurse care managers, case managers, or social workers can coordinate essential services for patients to return to the community and live at home. Services include home safety evaluations, delivery of medical equipment, and provision of in home and follow-up care. EDs with geriatric accreditation also have ED staff dedicated to geriatric care, provision of interdisciplinary teams, geriatric skills training for staff, geriatric-friendly policies, and quality improvement efforts focused on the care of older adults. GED accreditation is relatively new and the benefits to patient outcomes are still being studied. However, implementing GED accreditation standards that empower ED staff to manage older patients more knowledgeably and effectively can also improve ED providers’ ability to safely transition patients to home.

EDs do not have to make large-scale investments in transitional care immediately but can start with modest steps. These may include partnering with physical therapy or other departments connected to community-based care to provide consultations. They can assign a social worker to the ED part-time to gain insights into the impact of geriatric-oriented case management and community referrals on length of stay, discharge to home and returns to the ED. Other interim solutions to increase coverage or manage gaps in outpatient transitions include using telehealth to initiate geriatric assessments or initially placing the patient into observation until services are available the next day. These preliminary steps can help demonstrate the value of these services and build the case for dedicated resources and staff.

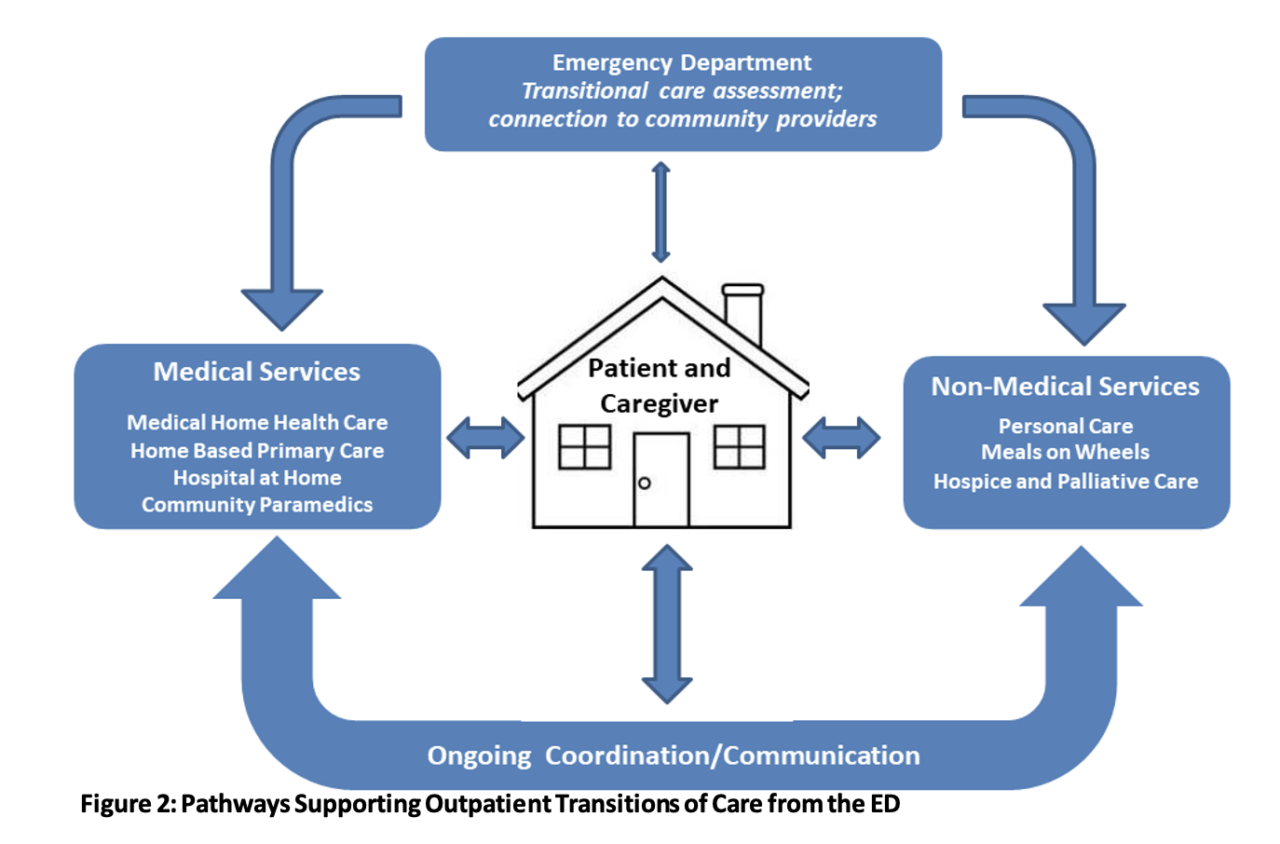

Table 1 is adapted from a paper by Robert Kane10 and describes a menu of possible home care services, current challenges in coordinating them from the ED, and potential solutions. These changes lead to a more integrated and coordinated system that provides a pathway to return patients safely to their homes with the support they need. (See Figure 2.)

While these suggestions primarily focus on what EDs can do, it is also important to note that broader systemic challenges remain. Home health services have historically had limited capacity and are under-reimbursed. For example, home care workers’ low pay and poor job quality has driven dramatic workforce shortages that will only increase without significant national and state-level investments.13 Advocating around these broader policy issues is also an important component of supporting transitions to home-based care.

What Does This Mean for Mrs. C?

The COVID pandemic has highlighted the urgency of enhancing home-based supportive services. For Mrs. C, the ED was able to help identify the cause of her acute illness. But, her refusal for admission introduced a need to balance her autonomy, preferences, and safety. Without clearly identified needs and a coordinated discharge plan to fill in the gaps, her health would likely continue to deteriorate, and Mrs. C would return to the ED.

Mrs. C’s COVID test was negative. She met with the ED’s care coordinator, who assessed her medical and social risk and asked questions about her home environment. The care coordinator worked with the ED physician to order oxygen delivered to Mrs. C’s home by community paramedics. The care coordinator was also able to enroll Mrs. C in a local Visiting Nurse Service with 24-hour admission, where she will receive timely follow-up from a nurse. Going forward, if Mrs. C’s mobility and COPD symptoms do not improve and she meets the Medicare criteria for being homebound, she can be enrolled in her hospital’s home-based primary care program. She can then receive home visits on an ongoing basis and may qualify for aide services to help with her self-care.

Mrs. C’s case demonstrates that reaching beyond the usual walls of our healthcare settings can be an important third option for the ED that preserves patient independence and provides high-quality, patient centered emergency care.

Key Wrap Up Points

- When hospital admission is less than desirable and sending a patient home alone feels unsafe, health and social services at home are a valuable third option.

- Coordinating home support services from the ED is effective care delivery and aligns with health systems’ goals of decreasing avoidable admissions.

- Developing capacity to assess and refer patients to home support from the ED is part of good emergency care.

- Change doesn’t have to happen overnight. Taking small steps now can help EDs build toward high-quality, patient-centered care for older patients.

Key Words

emergency care, geriatric emergency department, home health, home care, social work

Affiliations

Emily Franzosa, DrPH, MA

- Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York NY

- Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, James J. Peters VAMC, Bronx, NY

Ula Hwang, MD, MPH

- Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, James J. Peters VAMC, Bronx, NY

- Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Maya Genovesi, LCSW, MPH

- Department of Emergency Medicine, Social Work Services, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY

Orna Intrator, PhD

- Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY

- Geriatrics and Extended Care Data Analysis Center (GECDAC), Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Canandaigua, NY

Thomas Edes, MD

- Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC

Michael Malone, MD

- Senior Services of Advocate Aurora Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Milwaukee, WI

Acknowledgements

Corresponding Author – Emily Franzosa, DrPH, MA:

- Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York NY

- Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, James J. Peters VAMC, Bronx, New York

- Email: emily.franzosa@va.gov

Author contributions. All authors contributed to the conceptualization, research for, and writing of this commentary, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests: Michael Malone’s family owns stock in Abbott Labs and AbbVie. Dr. Malone also receives funding support from the Geriatrics Emergency Department Collaborative. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Sponsor’s Roles: N/A

Authors’ note: This paper does not reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

References

- National Research Council. The future of home health care: Workshop summary. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

- American Academy of Home Care Medicine. HBPC resources: A toolkit for healthcare partners. https://www.aahcm.org/page/hbpc_toolkit. Accessed March 25, 2021.

- Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Gilman CV, Jones J, Levy C. Caregivers create a veteran-centric community in VHA medical foster homes. Journal of gerontological social work. 2016;59(6):441-457.

- Holly R. New Hospital-at-home waiver program is ‘another step forward’ for home-based care. Home Health Care News. 2020; Nov 30.

- Morrison RS, Meier DE. Palliative care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(25):2582-2590.

- Abrashkin KA, Washko J, Zhang J, Poku A, Kim H, Smith KL. Providing acute care at home: community paramedics enhance an

advanced illness management program—preliminary data. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(12):2572-

2576. - Richardson LD, Hwang U. America’s health care safety net: Intact or unraveling? Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(11):1056-1063.

- Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, et al. The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. Santa Monica,

CA: RAND Corporation;2013. - McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Trepanier S, Verdon J, Ardman O. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: The ISAR screening tool. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47(10):1229-1237.

- NowPow. https://www.nowpow.com/. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Vol 323. British Medical Journal Publishing

Group; 2001. - American College of Emergency Physicians. Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program.

https://www.acep.org/geda/. Accessed May 13, 2021. - Campbell S. We can do better: How our broken long-term care system undermines care. Bronx NY: PHI; 2020.