Introduction

In 2020, the US Census Bureau released updated data on the United States aging population, which has grown by over a third (34.2% or 13,787,044) since 2010₁, driven by a variety of factors including aging of Baby Boomers, increased longevity and lower fertility rate₂.

A global pandemic of historic proportions has constrained the healthcare ecosystem in systemic ways that are still reverberating throughout the country and world: staffing shortages, staff burn-out, lack of in-patient beds, increased boarding times in the emergency department, and decreased access to preventative care services, among many other impacts.

Avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions for older adults is incredibly costly. It is estimated that potentially avoidable readmissions cost Medicare $17 billion a year₃. As a result, reducing potentially preventable emergency department (ED) visits and subsequent hospitalizations or readmissions has become a priority for Medicare and other value-based care organizations, as the reimbursement landscape shifts away from fee-for-service to value-base care₄.

Such a confluence of factors: the aging demographic, constrained healthcare resources, and changing reimbursement landscape, has resulted in many healthcare systems placing a wide-scale, strategic emphasis on caring for older adults.

Emergency Departments, specifically those that address the needs of older adults, are one tactic that healthcare systems are utilizing to reduce avoidable hospitalizations and connect older adults to appropriate outpatient resources. Recognizing the need to address the unique health concerns of older adults, in 2014 the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) created Geriatric Emergency Department (GED) Guidelines and soon followed with an Accreditation Program. Per the GED guidelines, a primary goal of the GED is to “recognize those older patients who will benefit from inpatient care, and to effectively implement outpatient care for those who do not require inpatient resources₅.”

Early adopters of healthcare system-wide GED accreditation include Advocate Aurora Health, Cleveland Clinic, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Kaiser Permanente, the Mayo Clinic, Northwell Health, University Health Network – Toronto, the Veterans Administration and Yale New Haven Health, among others. All of these systems have recognized that Geriatric Emergency Department accreditation throughout their healthcare systems will dramatically improve the quality of care older adults receive in their communities, while also resulting in reduced hospitalizations.

Purpose

What follows is a roadmap that provides an overview of these key steps necessary to successful system-wide implementation of GED accreditation. This roadmap was created for individual GED administrative and clinical leaders (MD, RNs) who are interested in the process of accreditation throughout their entire healthcare system but may not have any idea where or how to start the accreditation journey.

For information on how to implement an individual geriatric emergency department, please see: A Practical Guide to Implementing a Geriatric Emergency Department

Steps to Successful GED Accreditation Across a System

Collectively, early adopters of healthcare system-wide GED accreditation, have followed a similar six-step journey towards successful GED accreditation across their systems:

- Garner executive leadership support

- Build interdisciplinary and cross-site teams

- Generate Buy-In

- Integrate older adult triage, screening and treatment tools within standard workflows and electronic health records (EHRs)

- Begin and complete the GEDA Application Process

- Create standardized outcome metrics and management dashboards

Step #1 – Garner Executive Leadership Support

The first step towards successful system-wide GED implementation is to garner executive leadership support from your health system’s Chief of Emergency Medicine/Emergency Department Chair, Chief Medical Officer, and/or Chief Executive Officer.

To garner executive support, create a business case which clearly addresses the top priorities facing your executive-level leaders (ie: “C-suite”) and how GEDs are a tactic to support system-level strategies. Articulate how good geriatric emergency care translates to a broader vision (such as alignment with value-based care, improving quality metrics, reducing readmissions or enhancing the patient experience) and can solve pain points that your hospital or health system are currently experiencing. For example, GEDs can help optimize your hospital’s census management. If your hospital’s beds are full, GEDs can help direct patients to outpatient care settings, avoiding hospitalizations and thus freeing up space for higher-acuity and higher revenue-generating patients.

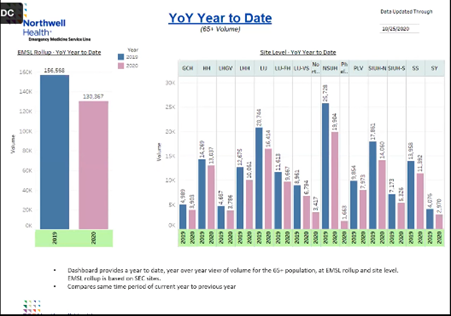

Make sure to provide data to back up your ideas in your business case. Articulate the need for a GED to serve your hyper-local patient population with census data on older adult patients, such as: total ED Visits for those 65+, average length of stay (LOS), 72 Hour Return Visits, 30 Day Return Visits, and ED Admissions for those 65+. For example, Northwell Health built a dashboard to show year-over-year, year-to-date, volume of ED visits per hospital for those aged 65+ when working with their executive leadership team to determine where and how best to prioritize implementation of GEDs across their system (Fig. 1).

Showcase impact of GEDs in your business case. There is a growing body of literature that supports the outcomes of GEDs to lower cost, improve quality and improve the patient experience:

- Up to 16.5% reduced risk of hospital admission₆

- Up to 17.3% reduced risk of hospital re-admission₇

- $3,202 savings per Medicare beneficiary after 60 days₈

- Decreased odds of 30 and 60 day fall-related ED revisit with PT services₉

- 3% satisfaction with the clarity of discharge information and perceived wellbeing₁₀

- 21 studies showcasing improved experience across a variety of interventions₁₁

- 25 hour decrease in length of stay for admitted patients₁₆

Finally, understand the financial impact of your proposal and the resources that will be required. Make sure your business case and elevator pitch are in language that executive leadership will understand. For additional recommendations about how to make your case to an executive sponsor, check out this toolkit.

Step #2 – Build an Interdisciplinary and Cross-Site Team(s)

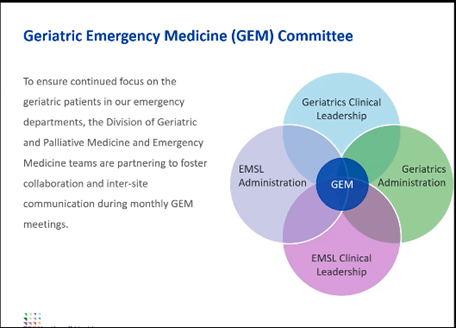

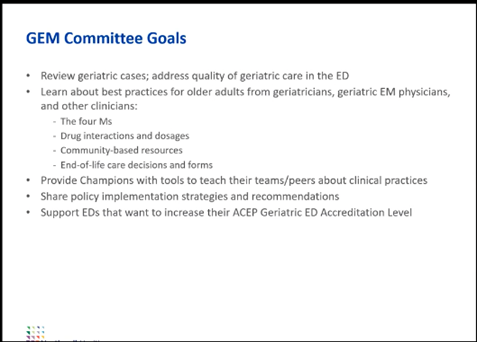

At a systems level, successful GED implementation is often led by an executive committee of multiple leaders responsible for implementation across the system. These groups often function as the administrative sponsors. For example, Northwell Health used a service-line approach with standardized policies and created a committee and partnership between the Emergency Medicine service line and Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, called the Geriatric Emergency Medicine (GEM) Committee (Fig. 2). The primary goal of the Committee was to ensure successful system-wide GED accreditation, but many other goals were a part of the Committee’s oversight (Fig. 3).

At an individual level, successful GEDs include: a physician champion or medical director and an identified nurse case manager or transitional care nurse. Physicians and nurses receive additional education in geriatrics that provides added expertise in the emergency care of older adults. GEDs are often overseen by a physician while the day-to-day operations of the GED are executed by a registered nurse or nurse practitioner, frequently referred to as a “nurse champion.” Successful GEDs also include multiple members of an interdisciplinary geriatric assessment team (intermediate care technicians, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work, pharmacy, gerontology).

In addition to an executive/administrative lead/sponsor, a physician champion/medical director, nurse champion, and multiple members of the interdisciplinary geriatric assessment team, successful interdisciplinary and cross-site teams also include a project manager and a data analyst. How you ultimately create interdisciplinary and cross-site teams will depend largely on the structure of your system, your local context and available resources.

Step #3 – Generate Buy-In

Creating buy-in is ultimately about influencing others to align with your vision and it will be important to generate buy-in with your executive leadership team, interdisciplinary team (including nurses and the larger clinical team) and external funders (if applicable).

Harvard Business School professor John Kotter is regarded by many as the authority on generating guy-in and managing wide-scale change. His 8-steps for leading change provides an easy-to-use and understand framework to begin thinking about generating buy-in amongst your stakeholders and ultimately leading the change of implementing geriatric emergency care throughout your system.

Much can also be learned from leading healthcare systems currently undergoing the effort to accredit all of their emergency departments as geriatric-friendly. The Veterans Administration shared some key elements to gaining widespread buy-in across a large system:

- Engage leadership and frontline staff

- Be mission-driven

- Listen to what matters and address it

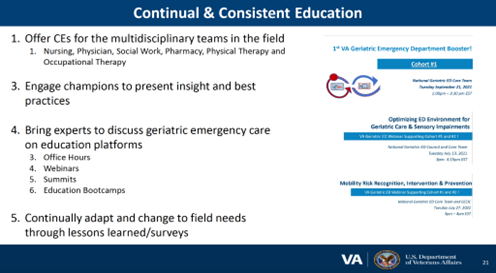

- Create education focused on the audience in the time and formats they want (Fig. 4)

- Recruit and engage champions

- Provide constant engagement by offering continued guidance, check-ins, examples and resources

- Recognition of team members that is personalized and congratulatory towards their accomplishments (Fig. 5)

Another key element of generating buy-in amongst your teams is by participating in shared decision-making. For example, anecdotally, Mount Sinai engaged with nurses about selecting the specific delirium screening tool to use, which led to higher levels of screen completion.

Step #4 – Integrate Older Adult Triage, Screening and Treatment Tools within Standard Workflows and Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

GEDA guidelines require “evidence of a geriatric emergency care initiative” or between 10-20 “policies, guidelines and procedures” to improve the care for older adults in the emergency department. An outsized emphasis is placed on triage and screening protocols. Working with a physician champion or medical director, a nurse case manager or transitional care nurse, the larger interdisciplinary team and an EHR engineer, to implement triage, screening and treatment tools within your standard clinical workflows and EHRs is required for GED accreditation.

Enhanced screening processes are important because they can quickly uncover physical or mental health risks that are more common in older adults. For example, screening tools uncover geriatric syndromes (like falls, polypharmacy, delirium, dementia) as well as social vulnerabilities (like food insecurity or elder mistreatment).

There are a variety of older adult triage, screening and treatment tools to choose from:

- A standardized delirium screening process (DTS; CAM; 4AT)

- A standardized dementia screening process (Ottawa 3DY; Mini Cog; SIS; Short Blessed Test)

- A standardized assessment of function and functional decline (ISAR; PRISMA-7; interRAI Screener)

- For additional information on screening tools for delirium, dementia and functional decline please view this article.

- A standardized fall assessment protocol (including mobility assessment, e.g. Timed Up and Go)

- An approach to identification of elder abuse (EASI)

“Implementing consistent screening and assessment requires careful planning, resource allocation, and modification of existing work practices to achieve its intended benefits.”₁₂ When you begin the process of implementing consistent triage, screening and treatment tools, there may be resistance that adding steps to the clinical workflow will seem overwhelming and time consuming. However, a 2021 study showed that “performing three geriatric screening tools took approximately three minutes of real clinical time” and that “performing screenings is feasible in a busy ED setting.”₁₃ An important first step to implementing a consistent screening and assessment approach is to create a clinical flow process map. For additional detailed steps on how to implement a consistent screening and assessment approach for geriatric care in your ED, please view this article.

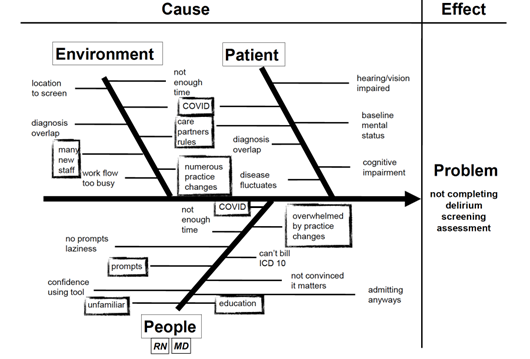

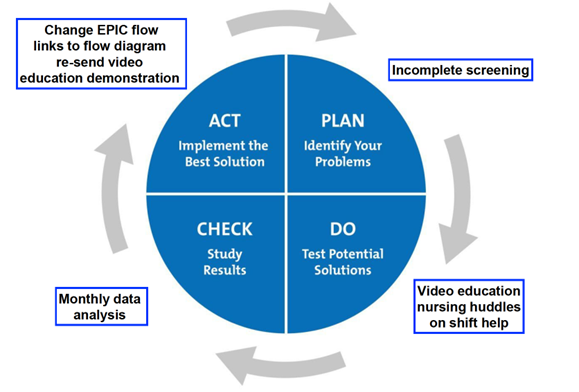

Once you have successfully implemented consistent triage, screening and treatment tools, you may find that adherence wanes over time. This was the experience of the Mayo Clinic as they sought to implement delirium screening across their GEDs sites. To solve this problem, the Mayo Clinic conducted a process analysis (Fig. 6), which showcased that a variety of environment, patient and people causes were affecting the completion of the delirium screening assessment. Then, the Mayo Clinic utilized the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycles to improve education and ultimately, adherence (Fig. 7).

Step #5 – Begin and Complete the Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation (GEDA) Application Process

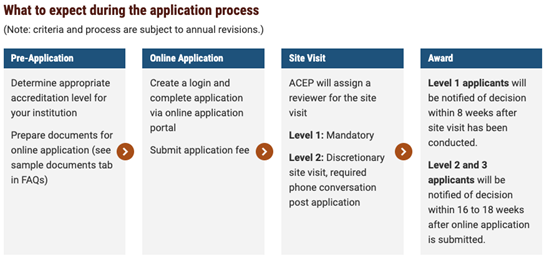

The Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation (GEDA) Program was developed by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to ensure that our older patients receive well-coordinated, quality care at the appropriate level at every ED encounter. The accreditation process has four phases:

- Pre-Application

- Online Application

- Site Visit

- Award

During the Pre-Application phase, determine the appropriate accreditation level for your institution and prepare your supporting documents for the online application.

Similar to the categorization of Trauma Centers, a Level 1 GED is the top level of accreditation and thus has the highest level of interdisciplinary and specially trained staff, policies, guidelines and procedures for geriatric emergency care. Level 1 GEDs must have at least 20 initiatives chosen from models of care that benefit older adults (e.g., a urinary catheter utilization policy) and quality improvement components, 5 outcome measures, availability of 10 equipment and supplies specific to older adults, and enhancements to the physical environment.

Level 2 GEDs provide many of the same enhancements as a Level 1, but on a smaller scale (e.g. only requires 10 geriatric emergency care initiatives) and often with fewer interdisciplinary and specially trained staff.

Level 3 GEDs require physician oversight, a nurse champion, and evidence of at least one geriatric emergency medicine care initiative. Oftentimes, hospitals begin the accreditation journey at a Level 3 and then “level up” as they build their infrastructure and gain core competencies in the operational and clinical requirements necessary to implement higher levels of geriatric specific emergency medical care.

For more detailed information about the differences between Level 1, 2 and 3 GEDs please visit: https://www.acep.org/geda/comparison-overview/

During the second phase, create a login and complete the online application via the online application portal, as well as submitting the application fee. Submitted applications will be reviewed for completeness by ACEP GEDA staff first, followed by a comprehensive evaluation by a team of ACEP-appointed physician reviewers. Next, ACEP will assign a reviewer to conduct a site visit. Finally, in the Award phase, applications will be notified of the final accreditation decision (Fig. 8)₁₄. The GEDA program managers are phenomenal resources to assist in your application preparation and submission. They can be reached at:

- Nicole Tidwell, GEDA program manager at: ntidwell@acep.org | 469-499-0149

- Bonita Marek, GEDA program coordinator at: bmarek@acep.org

Additionally, the Geriatric Emergency Department Collaborative (GEDC) offers consulting engagements to hospitals and health systems beginning their accreditation journey, or those seeking to achieve a higher level of accreditation. If you are interested in learning more about how the GEDC can assist you, please contact the GEDC.

Your strategy for applying for system-wide GED accreditation will depend largely on the structure of your system, your local context and available resources. For example, Northwell Health accredited all 17 GEDs as Level 3 at once. After Northwell Health decided to accredit all 17 EDs at once, they created and followed a standardized internal application process₁₅. A needs assessment guide was used by each ED leadership team to formulate their applications. The system-wide Geriatric Emergency Medicine (GEM) committee reviewed these applications for both individual merit and to ensure appropriate standardization across all applications submitted by the system.

For example, Northwell’s needs assessment revealed that “there were many policies and programs implemented to support the care of older adults, but much of this work was “siloed” within individual sites.₁₅” Then, Northwell decided to “aggregate all of the process improvement projects that were already ongoing within the EDs and assess which projects were most relatable to all EDs and which projects were more likely to be measurable using data from the electronic medical record (EMR).₁₅” As a result, Northwell highlighted their catheterization policy and catheter associated urinary tract infection reduction strategy for all GEDA applications.

Finally, Northwell’s GEM committee partnered with ACEP leadership to match all applications to the existing GEDA guidelines and created a feedback loop for incorporating ACEP feedback into each batch of applications.

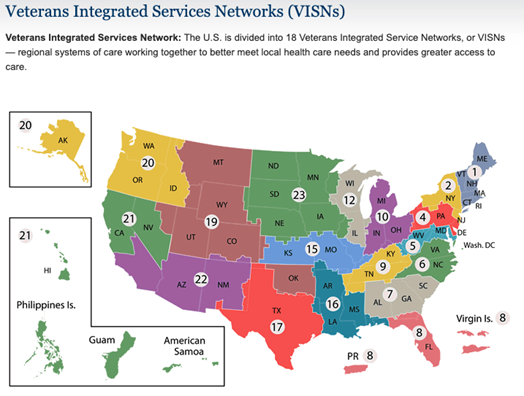

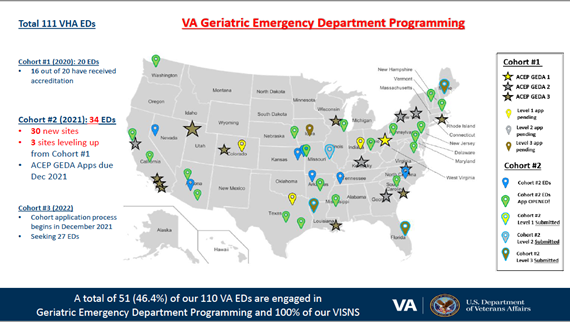

The Veterans Administration (VA) took a different approach to accreditation across their system. The VA developed a cohort strategy where accreditation has been rolled-out over time based on geographical service areas known as Veterans Integrated Services Networks (VISNs) (Fig. 9 & 10), due to the pre-existing administrative and leadership structures embedded within those service networks.

Step #6 – Create Standardized Outcome Metrics and Management Dashboards

The creation of standardized outcome metrics and other data management dashboards are important to understand success, opportunities, trends, and outcomes of treating older adults in your ED. It is important to assess progress in implementing older adult triage, screening and treatment tools within standard workflows and electronic health records (EHRs) that you instituted in step #4 in order to make any ongoing adjustments. Some standard metrics to consider tracking on your dashboard could include:

- % Completion of specific triage, screening and treatment tool(s)

- Older adult ED visits

- Length of Stay

- Admissions Rate

- Return ED visits

- Other metrics important to your health system or hospital, such as the patient experience

For an in-depth example of a GED Dashboard, please view this information session on the West Health GED Dashboard and how you can participate.

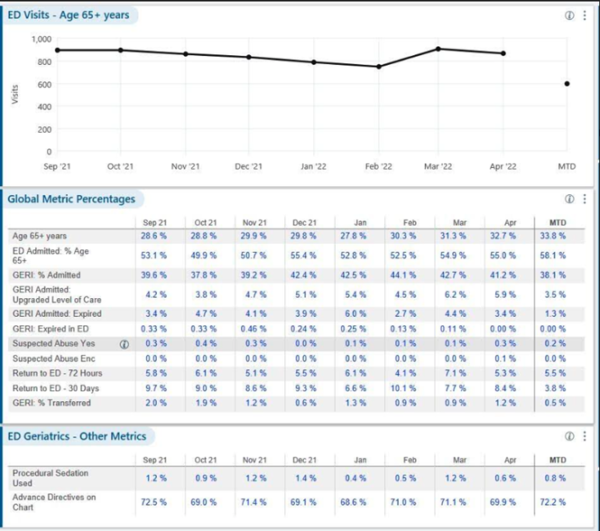

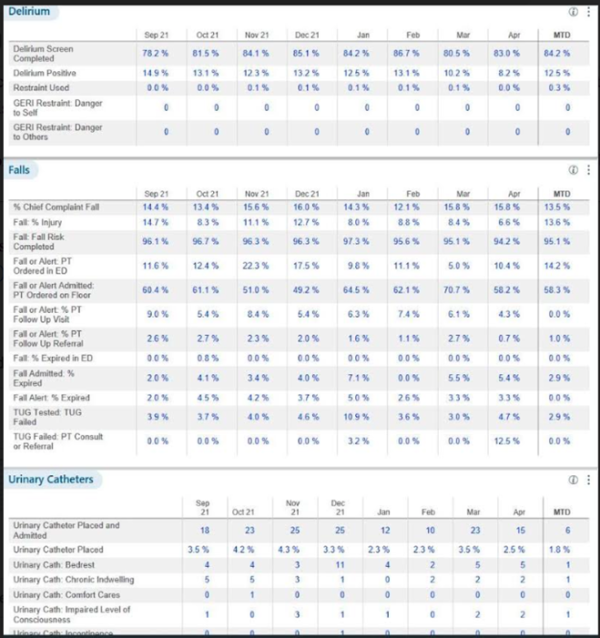

Oftentimes, a data analyst and/or an EHR engineer (in conjunction with a project manager) works in tandem with your physician and nurse champions to create these dashboards. Data analysts often use visualization tools (such as Tableau*) to create dashboards with data extracted from your EHR. The Mayo Clinic utilizes an extensive dashboard that tracks many metrics over time (Fig. 11 & 12), which serves as a great example to get you started thinking about what your dashboard could look like.

Conclusion

Many healthcare systems have begun to place a wide-scale, strategic emphasis on caring for older adults through achieving geriatric emergency department accreditation. Early adopters of this strategy have followed a similar six-step journey from which others can learn.

For more information on how you can become a Geriatric Emergency Department, please contact the Geriatric Emergency Department Collaborative.

*Any mention of products or tools does not represent endorsement by the Geriatric Emergency Department Collaborative and is instead merely reflective of what hospitals and health systems have mentioned that they use.

Figures

1. Northwell Health 65+ ED Volume Data Dashboard

2. Northwell Health Geriatric Emergency Medicine (GEM) Committee Structure

3. Northwell Health Geriatric Emergency Medicine (GEM) Committee Goals

4. Veterans Administration Approach to Continual & Consistent Education as a Way to Generate Buy-In

5. Veterans Administration Approach to Recognition as a Way to Generate Buy-In

6. Mayo Clinic Delirium Screening Process Analysis

7. Mayo Clinic PDSA Cycle to Improve Delirium Screening Education & Adherence

8. Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation (GEDA) Application Process

9. Veterans Administration’s Veterans Integrated Services Networks (VISNs)

10. Veterans Administration Cohort Strategy for System-Wide Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation

11. Mayo Clinic Data Dashboard Part 1

12. Mayo Clinic Data Dashboard Part 2

References

- Bureau, U. S. C. (2021, October 8). 65 and older population grows rapidly as baby boomers age. Census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/65-older-population-grows.html

- Roberts, A. W., Ogunwole, S. U., Blakeslee, L., & Rabe, M. A. (2018). (rep.). The Population 65 Years and Older in the United States: 2016 (pp. 1–25). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- Offices of Enterprise Management, & Brennan, N., Real-Time Reporting of Medicare Readmissions Data27–43 (2014). Washington, D.C.; CMS.

- Reyes B, Ouslander JG. Care transitions programs for older adults-a worldwide need. Eur Geriatr Med. 2019 Jun;10(3):387-393. doi: 10.1007/s41999-019-00173-5. Epub 2019 Feb 22. PMID: 34652789.

- ACEP, AGS, ENA, & SAEM. (2014). Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines. Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program. Retrieved September 1, 2022, from https://www.acep.org/geda/

- Hwang, U., Dresden, S.M., Rosenberg, M.S., Garrido, M.M., Loo, G., Sze, J., Gravenor, S., Courtney, D.M., Kang, R., Zhu, C.W., Vargas-Torres, C., Grudzen, C.R., Richardson, L.D. and (2018), Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations: Transitional Care Nurses and Hospital Use. J Am Geriatr Soc, 66: 459-466. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15235

- Dresden SM, Hwang U, Garrido MM, Sze J, Kang R, Vargas-Torres C, Courtney DM, Loo G, Rosenberg M, Richardson L. Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations: The Impact of Transitional Care Nurses on 30-day Readmissions for Older Adults. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Jan;27(1):43-53. doi: 10.1111/acem.13880. Epub 2019 Dec 1. PMID: 31663245.

- Hwang U, Dresden SM, Vargas-Torres C, et al. Association of a Geriatric Emergency Department Innovation Program With Cost Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e2037334. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37334

- Lesser A, Israni J, Kent T, Ko KJ. Association Between Physical Therapy in the Emergency Department and Emergency Department Revisits for Older Adult Fallers: A Nationally Representative Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2205-2212. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15469. Epub 2018 Aug 21. PMID: 30132800.

- Guttman A, Afilalo M, Guttman R, Colacone A, Robitaille C, Lang E, Rosenthal S. An emergency department-based nurse discharge coordinator for elder patients: does it make a difference? Acad Emerg Med. 2004 Dec;11(12):1318-27. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.07.006. Erratum in: Acad Emerg Med.2005 Jan;12(1):12. PMID: 15576523.

- Berning MJ, Oliveira J E Silva L, Suarez NE, Walker LE, Erwin P, Carpenter CR, Bellolio F. Interventions to improve older adults’ Emergency Department patient experience: A systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Jun;38(6):1257-1269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.012. Epub 2020 Mar 12. PMID: 32222314.

- Costa, A. (2021, May 18). 10 tips on implementing a consistent screening and assessment approach for Geriatric Care. GEDC. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://gedcollaborative.com/article/10-tips-on-implementing-a-consistent-screening-and-assessment-approach-for-geriatric-care/

- Elder, N. M., Bambach, K. S., Gregory, M. E., Gulker, P., & Southerland, L. T. (2021). Are Geriatric Screening Tools Too Time Consuming for the Emergency Department? A Workflow Time Study. Journal of Geriatric Emergency Medicine, 2(5), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://gedcollaborative.com/jgem/geriatric-screening-tools-time-consuming-emergency-department-workflow-study/

- ACEP, A. C. E. P. (n.d.). About the process. ACEP.org. Retrieved November 15, 2022, from https://www.acep.org/geda/about-the-process/

- Liberman T, Roofeh R, Herod SH, Maffeo V, Biese K, Amato T. Dissemination of geriatric emergency department accreditation in a large health system. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020 Sep 7;1(6):1281-1287. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12244. PMID: 33392533; PMCID: PMC7771769.

- Keene SE, Cameron-Comasco L. Implementation of a geriatric emergency medicine assessment team decreases hospital length of stay. Am J Emerg Med. 2022 May;55:45-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.02.027. Epub 2022 Feb 21. PMID: 35276545.